A Matter of Gravity: South Florida's canals can't take it any more

A story of explosive growth, unthinkable expense, and missed signals

Via CBS Miami. Driver in Hallandale Beach couldn’t distinguish between the flooded street and the flooded canal. June 13, 2024

If you wanted to make a movie that brought our country's climate adaptation shortcomings to life, South Florida would make a terrific subject.

So many layers: Much of the flood control infrastructure there was built many decades ago to handle a population 1/5th the size, and it's at or beyond its useful life. Although the very skilled professionals working for the South Florida Water Management District are hunting through couch cushions for money to patch up their existing systems, all they can do is prioritize: it will cost many billions to fix and replace what they're dealing with, and it's unclear where that money will come from. Worst of all, the news that sea level rise and intense storms will quickly be getting worse has not reached the Sunshine State: what they're planning to build, if the billions arrive, will likely be obsolete in short order.

All of this will have major consequences for homeowners and for the economy of the state—and the country. Surely we could do better in planning to protect American citizens.

The Central and Southern Florida flood control system was envisioned back in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s, and many components built back then are still in service. John Mitnik, Chief District Engineer and Assistant Executive Director of the South Florida Water Management District showed these images to the SFWMD board over the summer:

It's quite a web: 2100 miles of canals, 90 pump stations, 915 water control structures. And it was built for a different time. Here's what Brickell Point, in the city of Miami, looked like when construction of this drainage system started:

That same area now looks like this:

Miami has changed a lot since 1940:

When these systems were built, places like Coral Springs didn't exist; much of Broward County, north of Miami and now home to two million people, was empty, rural, and expected to flood during a heavy rainstorm.

The water management system that was built back then to get floods out of peoples' driveways and streets and homes is all gravity driven. Just let that sink in for a moment.

For water to flow away to the ocean from occupied land, there has to be enough of a head, or height, inland so that it will flow downhill, via gravity. But now the seas are rising, and frequently the "tailwater," the downstream ocean water, is higher than the upstream water. Result: nothing moves. Gravity can't do its work.

This chart shows the number of days a year since 1980 on which a canal structure in Miami-Dade County (S28) had tailwater that was higher than the upstream land side. Those numbers are climbing.

Also, these drainage systems can't handle more than about 6 inches of rain over a 24-hour period. Increasingly, South Florida is seeing ferocious storms accompanied by two dozen inches of rain.

Gravity alone won't do it. To actually remove water—to get it to the ocean—many pumps will be needed. Each one will cost about $150 million, and even then new pipes will have to be broad enough to carry an enormous amount of water, and even then the engineers will be essentially pumping the Atlantic back into the Atlantic. Which is tough.

It's worse than that. Not only are these elderly pieces of infrastructure insufficient to handle what's being thrown at them, they're also disintegrating. Concrete that has been sitting in water for decades is shedding aggregate, cracking and spalling, and losing its structural integrity. Mitnik ran through a horror show of images from canals in South Florida:

You can poke your fingers and arms into these voids.

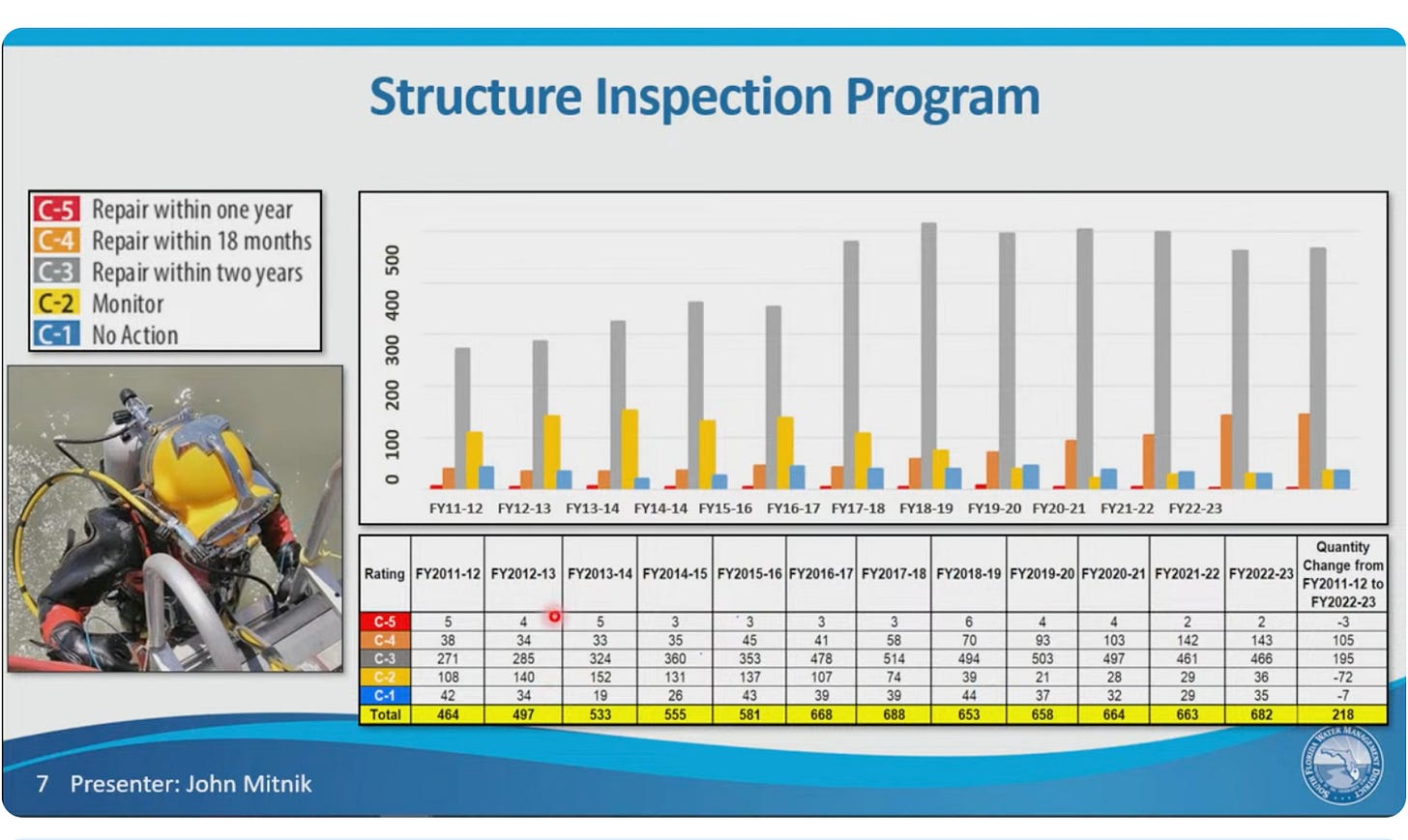

Mitnik and his colleagues are doing the best they can. None of this is news to them, and they've been steadily prioritizing structures for years, identifying the worst of the worst and slating them for improvement. The structures that are just about to collapse and fail are labeled "C5," and they try to deal with these. But there are many "C4s" and "C3s," built decades ago, that are in terrible shape and need to be fixed or replaced, and those numbers are growing steadily.

At the same time that fully 50% of the original flood control infrastructure has reached the end of its useful life, they're adding more structures, trying to keep up with incredibly rapid population growth and soaring land use: Since 2006, 84% more structures have been built, and 78% percent more pumps. It's quite a picture: major refurbishments are needed everywhere, and a lot of replacement has to happen, and meanwhile the storms keep coming—and they have to handle them with the decrepit gear they’ve got plus build more stuff.

How will all of this be paid for? Mitnik and his team are actively looking for money. They get some money from property taxes (about $150M this year, as far as I can tell). They ask for money from FEMA and the state. They try to find funding for many Army Corps studies. They're working with county and local governments right and left.

In September, they came up with a strategic plan that lists a zillion high-priority projects that, collectively, will cost nearly $4 billion. They list possible funding sources but from what I can tell no one is counting on this money arriving absent a disaster. In effect, the SFWMD is holding out its strategic plan as a vessel, ready to collect funds when they rain on Florida following the next cataclysm—which may not be the best way to plan ahead, but is the only path available.

It may not be enough. Although the SFWMD is looking hard at its infrastructure and planning to be ready should money come its way, what it builds will likely not last as long as anyone would like.

These Florida planners are assuming a "level of service" for their infrastructure that will accommodate (to some extent) two feet of sea level rise. (That is slightly lower than NOAA's Intermediate High projection.) Even this level of service will result in flooding when storms are heavy.

Level of service for flood protection, given 2 feet of sea level rise. Notice all the red around Miami.

But two feet is too low an assumption. Over the last few years, it has become increasingly obvious to climate scientists that predictions about sea level rise and increasingly ferocious weather along the East Coast are failing to take into account strong signals that rapid, nonlinear changes are coming soon.

Late last month, dozens of leading oceanographers sent a warning letter to the Nordic Council of Ministers saying that the presence of a distinct "cold blob" in the North Sea plus excessive warming along the East Coast of the US were strong signs that the ocean's conveyor belt of overturning circulation—the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Current, or AMOC—was slowing down. There's data documenting this trend since 1940. Here is Stefan Rahmstorf describing what's going on to the Nordic Council.

See that warming along our coast? That's one of the signals. We know that the slowing of this overturning will become so self-reinforcing that it will cause major sea level changes for the East Coast. Additional water will suddenly slop up over our shores. This crossing of a "tipping point" will most likely happen by 2050, according to current research. (Wally Broecker warned us of the potential for sudden and dramatic changes decades ago.) The models used by the UN underestimate this problem, as do those NOAA is using.

Millions of people now live in South Florida. At this summer's hearing, Ben Butler, a SFWMD governing board member, asked the Executive Director of the SFWMD, Drew Barnett, about the expense of all the planned building.

"Yeah, I mean, we've got inflation," said Butler. "You've got these five and ten-year capitalization budgets. Drew, are they attainable?"

Mr. Barnett responded: "I think the right question is, 'can we afford not to attain it?'...I mean, this is flood control for South Florida, right? I mean, everything is built on that."

Right. Everything is built on that. But is rebuilding it to a standard that may not anticipate the full suite of risks feasible? Sensible? Wise?

Great article, Susan. It’s past time for anyone in coastal areas to stop believing their own BS and continue kicking the climate change induced flooding can down the road. They knew more than 50 years ago that this day was coming but they rationalized their way into a temporary patch mentality with a blind hope that things wouldn’t be as bad as the research said it would. Oops!

The Netherlands faced this same music in the early 1950’s. Delta Works, the solution developed between 1953 and 1958, was completed in 1998 (39 years of construction) and requires continual maintenance. The cost was about $5-8 billion (about $25 billion in current dollars) and was spread over decades but represented a heathy portion of their national GNP and GDP.

Had they waited, their country would be faced with the same issues as South Florida and all other low lying coastal areas in the country are today: massive unpredictable storms, flooding, no drainage, large numbers of injuries and deaths and massive, billions to trillions of dollars in property damage.

But, Netherlands isn’t America. Americans cannot agree on education or healthcare priorities; how could or even would they ever be able to agree on massive projects like flood protection?

At this point, most of these low lying communities appear to be at the point of no return: the cost may be prohibitive, there isn’t likely enough time to develop and construct solutions, and a hodgepodge of private, local, state and federal interests, regulations, laws, procedures and capability limitations stand in the way, including money. Will a majority of Americans be willing to foot the bill for the billions to trillions of costs involved in places they don’t live?

Tick tock… The AMOC flood and climate change wolf is knocking on America’s and the World’s doors and howling to be let in. This wolf simply doesn’t care what or even if anyone believes it’s real, or not, or what anyone’s political party believes in. It’s coming.

I like your tone.