[from the Financial Stability Oversight Council’s Dec. 2023 annual report]

As global warming accelerates dramatically—now 67 percent more quickly than in the decades between 1970 and 2010—it's a good idea to pay attention to places in our intertwined financial system where risks of extreme weather may not be being taken adequately into account.

We know that failing to understand the physical climate risks faced by residential (and commercial) real estate can have enormous implications for the country. It isn't just the risks to the entities directly extending credit to the owners of risky real estate: The mortgage-backed securities (MBS) market is one of the deepest and most-liquid markets in the United States and a central element of our financial system. If mortgages melt, the poison will spread quickly into a broad array of financial corners, with dramatic consequences for the country's (and the world's) financial stability. And we know that the likelihood of large pulses of sea-level rise in the next 20 years is climbing quickly, threatening trillions of dollars in coastal real estate.

Here's a question someone asked me at the beginning of this week: Why are banks still giving out 30-year mortgages for risky properties?

You’d think thank banks would be wary of the risks involved. Well, it turns out that the institutions doing most of the mortgage lending in the US are automagically checking boxes. It’s unclear whether they are required to follow climate-driven guidelines. They then immediately shift almost all the risk to federal agencies. They're not "banks." They're "nonbanks.”

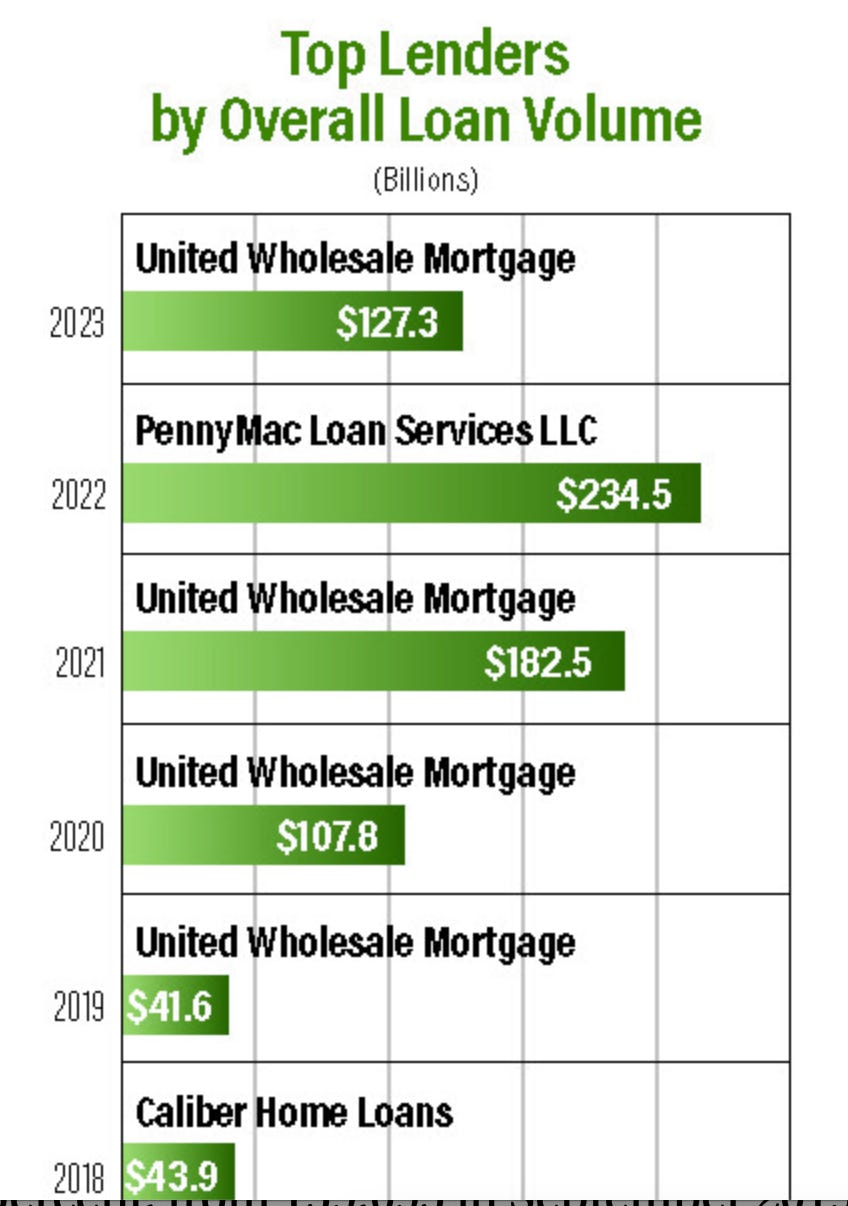

Nonbanks are huge in the mortgage business. United Wholesale Mortgage, Rocket Mortgage, and Pennymac Financial are all nonbanks. (Brief primers on nonbanks here and here.) They originated about 70 percent of single-family mortgages during the first half of 2023. They're doing this to generate riskless (to them) fees. They're not subject to real oversight, although that situation may be changing. And they're highly attractive to Wall Street: Goldman Sachs over the last year has been providing more financing to United Wholesale Mortgage, and according to the Wall Street Journal recently tried to make a deal with Rocket Mortgage.

If you ever want to worry about risks posed to the American economy at the intersection of climate and finance, keep your eye on the increasingly concentrated world of the nonbanks.

Following the 2008 financial crisis, the Dodd-Frank Act gave the Financial Stability Oversight Council the authority to designate nonbanks for supervision (meaning oversight) by the Federal Reserve. FSOC and Secy. Yellen have signaled that they're thinking of doing this for giant mortgage originators whose failures could threaten financial stability. That's probably a good idea—those designated firms would then have to maintain greater capital and liquidity.

But it may be too late. The risks are already out there in the form of possibly-to-be-defaulted-on mortgages sitting on the federal government's books (and thus all of our books). As we know, increasingly expensive and increasingly-narrowly-circumscribed insurance won't necessarily prop up the collateral for these loans in the face of chronic and climbing inundation.

These nonbank mortgage origination and servicing companies are truly marginal businesses: if there's suddenly a delay in selling loans to these government investors, or if a slew of borrowers defaults, they don't have a lot of money on hand and won't be able to handle big losses very well. They rely on short-term financing, like that Goldman line of credit, because they don't have deposits of their own. The banks reserve the discretion to cut off that credit. "In stressful times, their credit lines can be pulled," Secy. Yellen told Sen. Masto during a Senate hearing last month.

If they're in the business of servicing these mortgages (collecting payments, sending statements, handling escrow accounts for property taxes and insurance), and there are widespread delinquencies, these nonbanks may stay on the hook for these costs of these services and bills, even if homeowners can't pay. And they'll crumple.

This chart was a surprise to me:

[for 2022]

United Wholesale Mortgage is now bigger than Rocket Mortgage, and has been "winning" for years. I’ll use them as an example of risk, just because they’re listed:

What is United Wholesale Mortgage? It's not a bank, and it doesn't deal directly with home buyers. Its business is "originating" mortgages—taking in applications, verifying income, and assessing the property's value. UWM deals with mortgage brokers, who have their own customer relationships. After the loan is closed, UWM sells it on a few days later to Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, or to Ginnie Mae for securitization as part of MBS pools. In 2023, 93 percent of their loans were sold off UWM’s books in this fashion. In general, nonbanks provide more mortgages than banks, as a percentage, to lower-income people and people of color.

UWM makes money (10K here) from loan origination fees, from selling those loans to GSEs, and from servicing those loans—a total of about a billion dollars in "loan production" fees plus about $818 million in "loan servicing" fees in 2023. 2023 wasn't a great year for UWM, though, because the company also had huge losses in the form of markdowns for mortgage servicing contracts it sold off at a loss (perhaps to generate cash as interest rates soared last year, but you tell me).

From UWM's perspective, all of this is just fine. Here's Mathew Ishbia, UWM's Chairman and CEO, talking to analysts recently:

2023 was one of the best years in UWM's history. It wasn't the year that stands out from a financial perspective but will stand out from a dominance perspective. We separated from our competitors significantly on market share, growth, operational earnings and strategic investments.

It was our second year as the #1 overall lender. It was our third consecutive year as the #1 purchase lender and our ninth consecutive year as the #1 wholesale lender. As you heard me say many times before, the best mortgage companies shine in high-rate markets, and that's exactly what we have done consistently here at UWM.

Ishbia sees the moat around his business in the form of software:

[O]ur investment in technology continues to give our brokers a competitive advantage on speed, price and process, always making the process faster, easier and cheaper as our focus. The gap between UWM and our competitors is only getting larger. It's becoming that much harder to catch up, given our relentless effort to continuously improve.

UWM's process is completely tech-driven: it knows the address of a property, and it knows whether it's in a FEMA floodplain (and thus requires flood insurance), but as far as I can tell that's all it knows. Physical location or climate risk probably isn't a direct factor for UWM beyond those maps. We know many of those maps are inaccurate. I would love to be wrong about this. It does seem as if Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac are adopting risk screenings that go beyond the FEMA maps. Have these predictions been incorporated into UWM’s work? I can’t tell.

UWM's streamlined, optimized process is designed to ingest as many mortgage applications as possible that will meet the GSEs' guidelines, and then sell them as quickly as possible, pocketing the difference between the interest rate they offer to the customer and the rate they offer the GSEs. Its primary focus is on the borrower's financial riskiness. It has every incentive to keep its factory of originations going, without regard to location. I searched UWM's 10K for the word "climate" and didn't find it.

To their credit, the financial regulators are focused on nonbank risks as well as climate risks. They are also beginning to consider these risks together. A report from the oversight committee's nonbank mortgage servicing task force was expected this month and will undoubtedly emerge soon.

==

Customer: "Excuse me, do you have any rolls of quarters?"

Teller at a nonbank financial institution: "I'm sorry, we don't have any quarters, but we can offer disruptive financial solutions!"

I know, weak.