Catastrophic uncertainty

When a warning gong is more than a warning

The possibility of bad weather outcomes for Charleston SC is high this afternoon. It looks as if Idalia will arrive in Charleston as a Category 1 hurricane around 8pm tonight, accompanied by very high winds, heavy rain, and possible tornadoes.

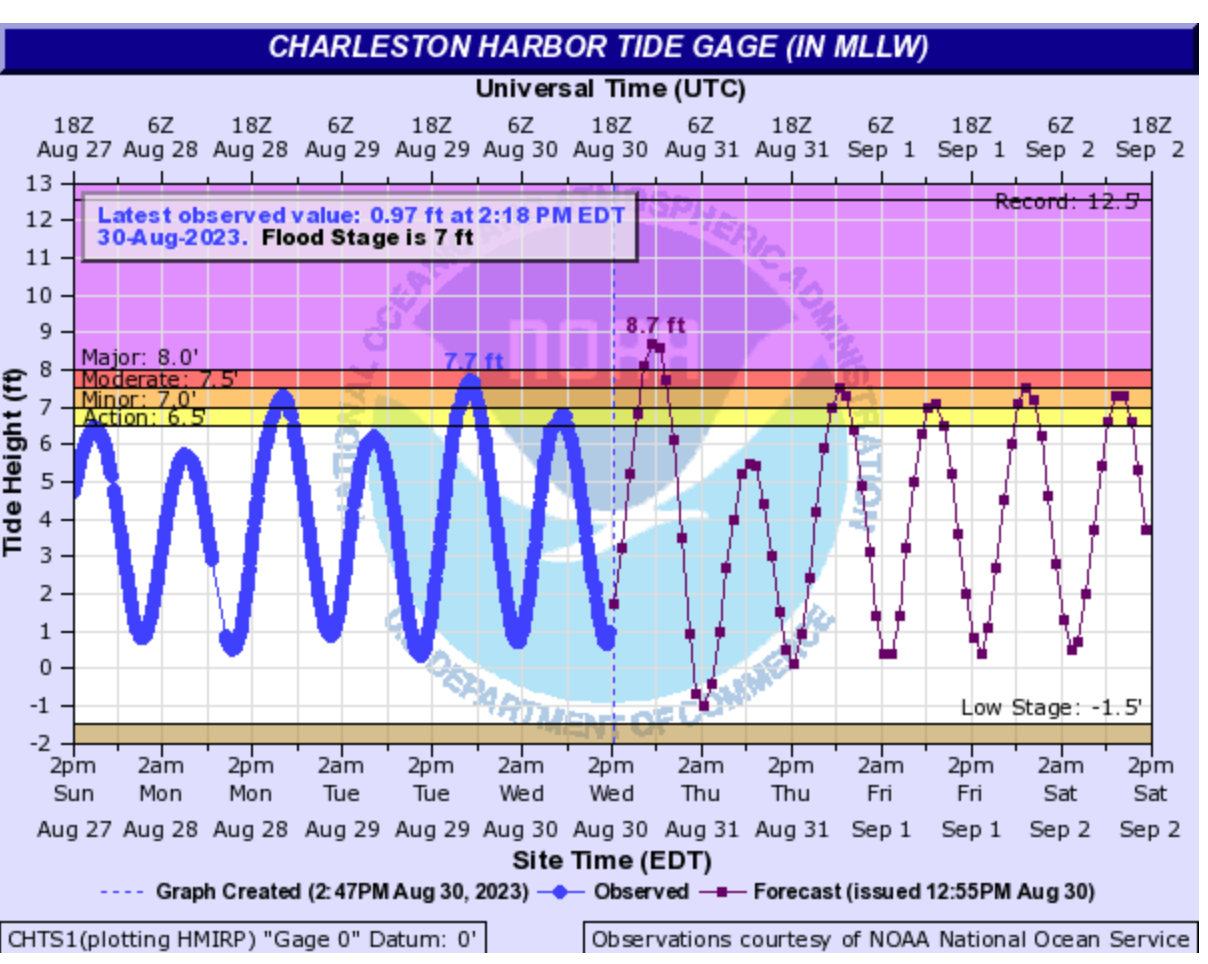

The bad news for Charleston is that the storm will hit at about the same time as one of the highest high tides this year at 8:24pm—one of the top fifteen tides ever to enter Charleston Harbor. The label for this particular high tide is a "king tide," a nonscientific but widely used term for a high tide driven higher by a full or new moon's arrival close to the earth. Indeed, you could pile up the appellations and call this a "super blue moon" tide, because tonight's is the second full moon in a month.

Any high tide over 7 feet slops onto Charleston's low ground, and today's particular high tide is predicted to be 8.7 feet. Even without a storm coming around.

So the City of Charleston will likely experience a trifecta of misery tonight: very powerful wind and rain arriving at the same time as a high tide that, all by itself, would cause major, debilitating flooding in the city. (Tony Bartelme of the Post and Courier calls this a “tropical trifecta.”) That flooding will be even worse because of the hurricane, which will be dumping heavy rain from above and blowing in wind-driven water from all sides. The hurricane's storm surge will be worse because its waves will be riding toward shore atop a very high tide.

The storm's destructive intensity, in turn, has been greatly amplified by the extraordinarily warm water over which it has traveled. Idalia is one of several recent storms that have rapidly intensified before hitting the U.S.

Yesterday, the Charleston City Council held an emergency meeting to prepare for Idalia's arrival. Following the invocation ("We ask that you'll just calm this storm, that you'll calm people's fears, and that you'll protect us, Lord"), Mayor Tecklenburg said that he was hoping that Idalia wouldn't arrive at the same time as the blue moon tide. "Maybe the impacts will be more at the outgoing tide, or low tide, which would be a blessing for us," he said. And maybe, he said, Idalia would just "be a tropical storm by the time it gets to South Carolina, and not a full force hurricane." Mayor Tecklenburg was clearly hoping that nothing awful would happen: "I'm really, frankly, very hopeful that the impacts of this storm will be minimal, and less than some of the other storms we've seen," he said.*

Ben Almquist, the city's Director of Emergency Management, gently steered the council toward considering the hazards ahead: "We're looking at impacts of flooding that are going to be more in line with what we receive with a category one hurricane," he said.

Well, that was yesterday. Now Idalia is a category one hurricane, and it's coming to Charleston at the same time as an extremely high tide.

==

By 2050 or so, because of the same forces that are intensifying the hurricanes and spurring on the wildfires already afflicting America (Maui seems so long ago), it is likely that a "normal" high tide along the southeastern coast of the US will be at the level of a king tide. It is likely that there will be even more frequent and more destructive storms. It is likely that high tides and increasingly destructive storms will, ever more frequently, arrive at the same time.

Now, it is not certain that these things will happen. Both the IPCC and NOAA are reluctant to claim they know exactly what is coming. They're cautious. There is apparently just one climate model pointing to the high probability of higher-end sea level rise projections and incorporating Antarctic melting. (Jeff Peterson of the Coastal Flood Resilience Project filled me in about this.) Because there aren't two models, the scientists feel they need to say that although it's plausible that areas along our coastlines will become unbearably, miserably, chronically flooded in short order, they have "low confidence" in these predictions. This makes it easy for policy makers to ignore the possibly "fat tails" of the distribution of climate events—the possibility that extremes will increasingly be ordinary.

Faced with uncertainty, what's a government official to do? One reaction might be to appeal to any deity we can think of to help us. Another might be to hope that everything will turn out fine in the end, that the storms will turn gently back into the Atlantic, that the winds will blow themselves out over other oceans, or that most of the high tides will be somehow manageable when we are ready to manage them.

A third approach might be to consider that we may "not be making nearly as big a deal of climate change as we should." That's the suggestion made by Geoff Mann in a current piece. Mann is pointing out that we use models based on a breathtakingly invented set of parameters in order to comfort ourselves that we know exactly what we're doing.

In the rapidly accelerating hurricane/storm surge/SLR/flooding setting, Mann's point could translate to (1) being up front about the fact we don't know exactly what will happen, (2) noticing that we are dramatically under-prepared for the possibility of awful outcomes, and (3) acknowledging that we have been far too confident that what we're doing is at all sufficient. And then changing our ways.

It may be that Idalia hardly ruffles Charleston tonight. But it also seems likely that Idalia is just the first warning signal of this hurricane season and all the seasons to come. The window for protecting residents may close sooner rather than later. We don't know exactly when that window closes, but that hardly seems a reason not to act.

==

* During yesterday’s emergency session, Mayor Tecklenburg helpfully noted that the storm's name was pronounced ee-DAH-lia, not eye-DAY-lia, as he had originally thought.