Everyone is talking about Greenland

So let's seize the moment to talk about melting glaciers and rising sea levels

Visiting remnants of icebergs in Greenland, July 19, 2024

The news from Greenland is extraordinary right now. It's always extraordinary these days. I’m not talking about Mr. Trump’s annexation plans. I’m talking about the climate. The Arctic has entered a "new regime" of heightened extremes that will never be stable again.

One day last week, nighttime temperatures in Greenland were 36 degrees F above normal. It was 52 degrees F that night, which is warmer than it usually is in July. Unbelievable air temperatures in the Arctic were accompanied by records in sea-ice extent (the lowest recorded for any February) and volume (second-lowest).

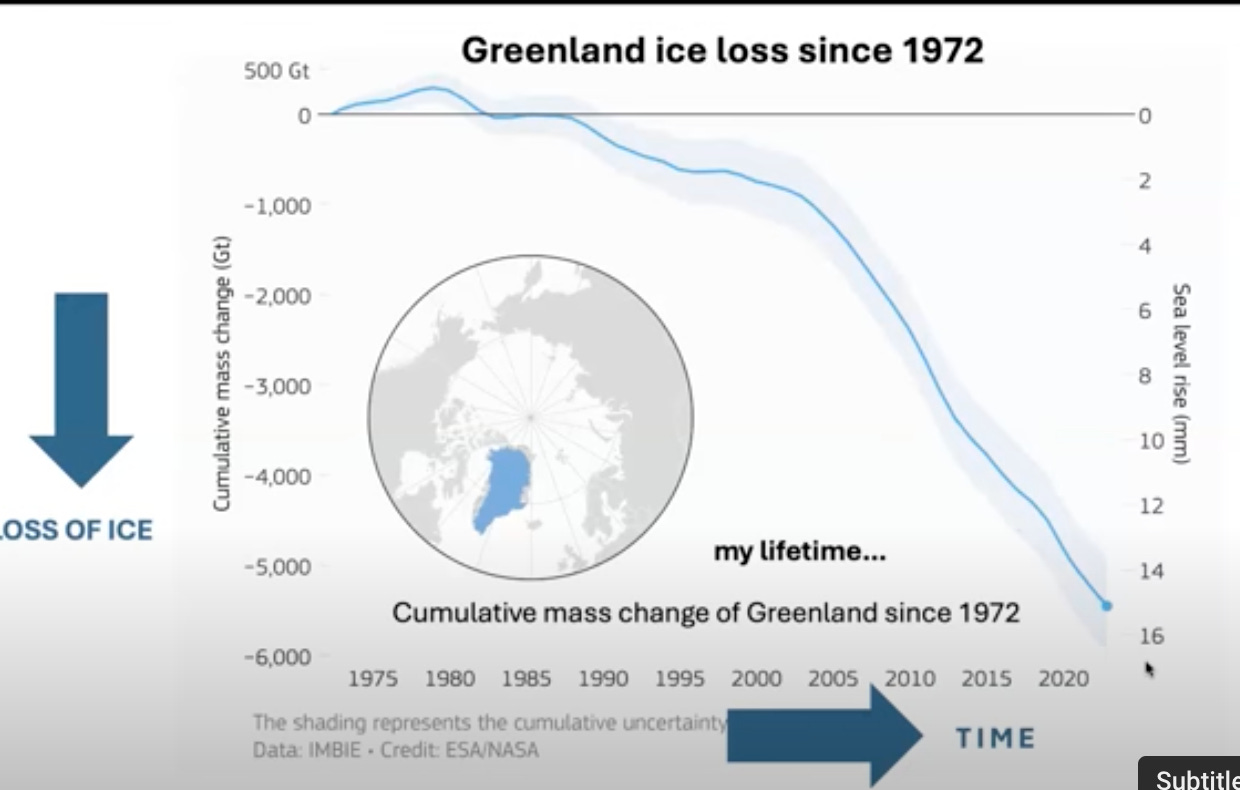

What is happening to Greenland, home to the Northern Hemisphere's greatest volume of land-based ice, is connected to what happens in every part of the globe. Changes are taking place extraordinarily quickly: When I was a child, the ice sheet covering Greenland was stable, with snow coming in matched by melt going out. Since then, and particularly since the 1980s, thousands of gigatons of ice have left Greenland.

Sarah Das, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution

Water that has wormed all the way through Greenland's ice sheet is causing ice to slide along bedrock toward the sea. Ice meeting warming oceans at Greenland's edges is breaking off. The speedy warming of the Arctic—four times faster than the average around the globe—is altering jet streams that now lock in place, spawning forest fires and floods. Greenland is now leading the way as a contributor to global sea level rise, and if emissions continue its rate of melt will approximately double beginning in a couple of decades.

And there's more: the freshwater held within this ice is changing ocean currents that drive our relatively stable climate around the world, allowing warm water to pile up around Antarctica. At some point, Antarctica, which holds ten times the amount of ice that Greenland does, will take the lead in contributing to sea level rise as its below-sea-level ice melts in response to the warming water flowing under and around it. This will have enormous implications for the East Coast of the US, because it will absorb the impact of sea level rise from Antarctic melt. The East Coast is already seeing sea levels rise more rapidly than most of the rest of the globe.

Perhaps the sudden global focus on Greenland—even if we're talking now somewhat abstractly about its sovereignty and territorial integrity—will prompt people to pay attention to the extraordinary physical climate risks its dynamic condition presages. At the least, getting Greenland into the conversational mix will help us in the decades to come, when people try to reconstruct why cities along the East Coast are chronically flooding.

We will be looking for explanations, I predict, because right now we've got a confusing set of communications.

Climate model scientists, actuaries, and ordinary people all have different ways of looking at risk. The conflicts between and among these ways of thinking are leaving regular people hoping for the best while failing to plan for the worst.

The climate scientists are part of a discipline that emphasizes certainty: they are focused on accurate measurement, and identifying what they can of underlying processes that explain those measurements. So although they will certainly identify extreme risks, they will be focused on emphasizing whatever certainties their research shows. Actuaries, by contrast, are professionally accustomed to identifying extreme but uncertain risks and asking whether businesses or people are set up to survive them.

In the case of Greenland, the dynamics of air, water, heating, and ice are complex, interacting, difficult-to-model processes. Scientists will say privately that the ice melt happening now was not supposed to happen for decades, according to their models. About twice as much sea level rise around the globe happened in 2024 than was predicted, and current consensus models likely don't adequately account for polar ice sheet destabilization. But their profession keeps them focused on building new models rather than waving their arms about the extreme risks they see around them.

The actuaries are aware of extreme physical risks and are trying to understand how to avoid or manage them; their professional lens is precautionary. This is why State Farm General wants to charge more for home insurance in California, why global reinsurance is becoming so expensive, and why actuary-at-heart Warren Buffett wrote frankly about accelerating extreme climate risks for the insurance industry in his recent shareholders' letter.

What's an ordinary citizen to do, given the mixed messages from climate scientists and actuaries? Humans usually systematically overestimate the dramatic effects of new developments in the short term and underestimate their effects in the long term. Early stories about the advent of the internet, the economic effects on nations of increasingly aging populations, and the consequences of artificial intelligence featured grandiose, eye-popping claims of immediate transformation. (1965: "Machines will be capable, within twenty years, of doing any work a man can do.") Early climate discourse featured similar rhetoric that may have prompted scorn when breathless predictions didn't come true. But now the effects of online communications, aging populations, and AI are being felt by almost everyone.

We may be at an ordinary-conversation turning point when it comes to the effects of climate change. This year, 2025, we seem to be past the stage of easily-dismissed doom and gloom, and deep into the reality of punishing weather and almost continuous extreme events.

Meanwhile, a lot of people are talking about Greenland.

Next time Greenland turns up in conversation, remind people: it is getting very warm there, and cascading, compounding effects are much more likely as a result. The real risks of water from the sky, rivers, and oceans are extraordinary.

Elderly iceberg surrounded by clear ocean and sunshine, Greenland, Jul. 2024

Excellent article Susan. You connect the unprecedented melting in Greenland with rising water levels worldwide, and the threat to community finance and risk management. The world is changing faster than most recognize. Kudos for the enlightenment.

We like simple explanations and yet the Greenland Ice Sheet is comprised of glaciers that will have differing types of responses-even if their story is the same overall-volume loss. I wrote a piece on this in 2011 for Skeptical Science (https://skepticalscience.com/Variations_in_Greenland_Glaciers.html)

and a paper by Moon et al (2014) did a good job of quantifying this thought. At that time many researchers were too focussed on having a singular model to fit glacier response.