FIRE weather: Big insurance companies can see the risks on their books, but banks can't

Why the insurance crisis in California is really a pockets-of-risky-properties crisis

[Wildlife-Urban-Interface overhead image, National Park Service]

I wandered through my school-age years in Southern California. I don't live there now, but I remember gentle sunny mornings, the sweet smell of the air, and riding my bike everywhere, every month of the year. I became aware of the world just barely in time to notice the sprawl of post-World War II bungalows across what had been orange groves and foothills, and to see the beginnings of development in far-flung canyons. I remember seeing those changes as raw and new.

Now, of course, it's just the way things are: The state's population has doubled since 1970, and, for a lot of reasons, much of that growth has happened in less-expensive areas far from city centers that bump up against densely-forested places—like San Bernardino County (226% growth between 1969 and 2022), east of LA, where my father taught at UC Riverside for 25 years.

Last month, San Bernardino County's Board of Supervisors issued the local-government equivalent of an anguished cry of despair, calling on the governor and the state legislature to declare a statewide state of emergency and to "take action to strengthen and stabilize the homeowners and insurance marketplace." Why do this? Because with a state of emergency in place, insurers would have to keep renewing homeowners' policies.

There's an ongoing crisis in the FIRE economy of California—the intermingled industries of Finance, Insurance, and Real Estate. Right now, the insurance part of that economy is ahead of the finance sector in understanding its risk. As wildfires increasingly ravage the state, and pockets of risky real estate become difficult for people to either sell or maintain, what looks now like an insurance problem will inevitably be understood as a debt and equity problem.

Leadership is sorely needed to navigate this ongoing transition. The first step is for someone in power to make clear that this is not, really, an insurance crisis.

When it comes to the home insurance sector of the FIRE economy in California, the quick summary goes like this: Private insurance companies with insights drawn from fine-grained data see the risks and are re-pricing their products or withdrawing altogether from high-risk areas. That's what's prompting San Bernardino County to yell and California's Department of Insurance to tie itself in knots in efforts to synthesize a functioning marketplace while simultaneously ensuring that insurance remains affordable.

Meanwhile, the insurer of last resort, the FAIR Plan Association, is absorbing more and more of these high-risk properties and growing faster than any other insurer in the state. It's becoming a large pool of concentrated high-risk policies. Because the FAIR Plan is actually a group of all the insurance companies doing business in the state, when it can't pay its claims it assesses those insurers to pay their share. Right now it's facing $340bn in exposure against just $250m in cash, so a single $8bn fire around Lake Arrowhead would wipe it out.

If I'm an insurer in California, I'm thinking "How long do I want to stay there getting an increased burden of these policies no one else wanted to write?"

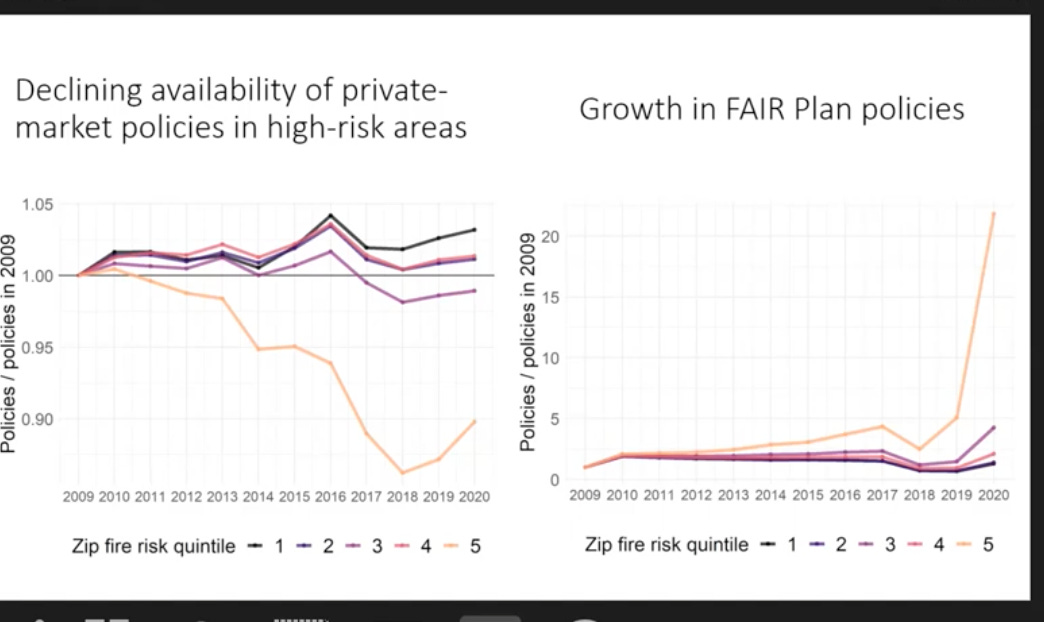

[Charts from a recent paper showing higher-fire-risk policies being dropped by the private market and absorbed by the California FAIR plan, through 2021. The picture has only gotten worse since then.]

State Farm, Allstate, and other insurers have announced they won't issue new policies for California homeowners because of wildfire risk. State Farm, the largest insurance company in the world, and the one with the biggest market presence in California, has asked for a 30 percent rate increase—right after getting approval for two other substantial rate hikes earlier this year.

The California Department of Insurance is trying to put in place a new set of rules that would allow insurance companies to both use sophisticated forward-looking models and pass through their reinsurance costs in their rates—but only if companies promise to keep up their relevant market shares in "wildfire distressed areas" and take policies off the FAIR Plan books. It's complicated, there are loopholes, and no one is satisfied. California is a big, risky state to keep happy, and right now it's a messy place for an insurer to operate.

But let's focus on FIRE and why this isn't really an insurance crisis. To the large insurers in California—particularly State Farm—the business risk of continuing to write policies for homes in the state is visible. According to an interesting paper that came out last month ("How Are Insurance Markets Adapting to Climate Change? Risk Selection and Regulation in the Market for Homeowners Insurance," by Boomhower, Fowlie, Gellman, and Plantinga), State Farm's rate filings show that as of 2021 the company was taking 434,252 variables about individual properties into account in pricing premiums, and very accurately predicting its losses in high-risk zip codes.* They've got the specific data that gives them these fine-grained insights.

[Chart showing that State Farm uses a mountain of information to set prices at the property level for home insurance, and that the statistical model used by State Farm fits the actual data on wildfire risk extremely well. As of 2021. From Boomhower et al., 2024.]

By contrast, banks issuing mortgages or loans for real estate don't, by and large, have these same insights. They are mostly blind to the physical risks burdening the assets on their books. Why? Because no one requires them to understand these risks, and it's expensive to do the first-rate modeling that is at the core of insurance companies' business models.

Even larger banks—banks with more than $100bn in assets, overseen by the Federal Reserve—are under no obligation to understand these risks. They must be hoping that insurance companies (or borrowers) will make them whole if their collateral melts away. But if the insurance company is the FAIR Plan, that doesn't sound like a great path. At the least, they should understand the risks embodied in their loan documentation (and their MBS holdings).

The Federal Reserve could re-characterize understanding these risks as part of its "financial stability" supervisory mandate. That's what the European Central Bank does. But we are not there yet, and Loper Bright looms.

So people continue to move into and stay in risky places and banks continue to issue and maintain risky loans. Insurance companies with better information are cutting their losses and exiting. Banks are plodding ahead, keeping their heads down and ticking the box for "insurance" when it's provided by the FAIR Plan, which, in turn, is struggling to handle incoming requests for its expensive, thin coverage. And the fire season is booming.

[Smoke rises from the Vista Fire as seen from a flight into Los Angeles International Airport on July 9, 2024. The remote location of the fire in the San Bernardino National Forest was making creating containment lines difficult. (AP Photo/Corinne Chin)]

Here's a description from John Vaillant's must-read book, "Fire Weather":

When a wildfire enters a residential community, the result—for the fire—is a smorgasbord of kiln-dried fuel topped with tar shingles, garnished with rubber tires and gas tanks. Meanwhile, the result for homeowners is shock and disbelief as the very structures designed to provide comfort and shelter turn on them in the most frightening way possible. ... As homeowners in these regions [including the American West] are learning every summer now, when the [Wildland Urban Interface] burns, it does not burn like a forest fire or a house fire, it burns like Hell.

There is no "insurance regulatory fix" for this. It will take leadership to put the intermingled risks of this situation on the table. It will take a swift leveling of the informational playing field so that more actors in the FIRE economy understand their real risks.

Perhaps that leadership will emerge when pockets of properties heavily damaged by wildfire end up in foreclosure proceedings, infecting the solvency of banks and local governments. Many people will suffer along the way.

*The paper also shows that insurance companies like Nationwide that use only crude, simple measures of property-level fire risk end up charging an enormous amount for policies in high-risk areas—and then are prone to quickly dropping new policyholders once a claim is filed.

This is "adverse selection" or the "winner's curse": Nationwide manages to sell coverage, but ends up with disproportionately high-risk properties because it doesn't have enough information to discern those risks. And then cuts and runs.

I’ve lived through nine of the ten largest fires in California history, all here in NorCal where I have lived for … coming up on eight years. What can’t be protected can’t be insured, a lesson we’re learning in parallel with Florida. It’s great to get the facts AND implications in one neat package.