Florida Man Plans to Rebuild. And Then Build More.

Why the baseline risks of property repricing in Florida are extraordinary

Much of the damage caused by Hurricanes Helene and Milton in Florida was greatly amplified by the effects of climate change—as much as half the damage can be attributed to accelerating warming caused by greenhouse gas emissions. But Florida also stands for a broader and more troubling story: Explosive growth there—an 18% population increase since 2010, compared to 7.7% for the country as a whole—is running straight into climate risks that should have been on the table years ago.

Now smarter, better-resourced insurance companies, recognizing these risks, are cutting their losses and finding other markets. In response, pockets of property markets are beginning to reprice. But the signal of risk, muted by banks' eagerness to lend, the state's eagerness to compete for economic growth, and the American belief that anything is possible, still isn't quite reaching Florida Man.

In Pinellas County, where St. Petersburg sits along the Gulf Coast west of Tampa Bay, nearly 41,000 homes were damaged by Helene and Milton, and about 170,000 people applied for help from FEMA. The county’s entire population is about a million.

Those same homeowners in Pinellas County are being squeezed from several directions: Not only is their region being ravaged by storms that damage their communities and their quality of life, but the cost of owning a house is climbing at the same time that the value of that house is sinking. Some of these homeowners will not be able to withstand this economic vise in the years to come.

The first mover in this story, the first sector to reprice, is insurance. You can't move an economic muscle without insurance: you can't drive a car, hire an employee, serve a client, or finance the purchase of a home without an insurance policy in place. But private insurance companies—especially larger, better-informed firms—are repricing and leaving Florida. In May, the state Insurance Commissioner said that Florida has a "strengthened and reliable insurance market for policyholders,” but he may have been talking about tort reform. At any rate, the increase in exposure caused by Debby, Helene, and Milton can't have helped.

What's left behind is Florida's state insurer-of-last-resort, Citizens Property Insurance Corporation, offering narrow coverage, high premiums and deductibles, and pulsing with insolvency risk. Citizens is the leader by far among all state insurers-of-last-resort, accounting for about 69% of direct premiums collected and 53% of all policies written by state residual plans across the United States (AM Best).

Tens of thousands of claims are landing on Citizens right now following Milton. Whether they'll be paid or not is an open question: the insurer didn't pay a nickel in response to 77% of the claims that followed early August's Hurricane Debby, probably because of Citizen's high annual deductible and because its policies don't cover flood damage. Much of Milton's damage was caused by storm surge and flooding (Claims Journal).

Homeowners in Pinellas County, the most densely-populated county in Florida, pay the highest average property insurance premiums in the Tampa Bay area: an average of $3,687, according to state data. In Hillsborough, the average is $3,203, while in Pasco it's $2,594, and $2,246 in Hernando.

Many homeowners pay several times this amount, depending on where their houses are, how big they are, and how new their roofs are. Those rates will keep climbing, perhaps steeply, in 2025, when reinsurers sharply raise premiums and pass those costs along to primary insurers. For some people, the overall price of maintaining a home in St. Petersburg won't be sustainable in the years to come.

At the same time, the quickly-growing Tampa region is one of the metro areas around the Gulf where real estate markets are seeing straight-out home price declines. Prices in St. Petersburg are 2.6% lower this year than last year, homes are sitting on the market longer, and nearly 40% of list prices for houses have to be lowered in order for sellers to find a buyer (Redfin). These pockets of softening aren't yet being seen in coastal regions in the Northeast:

Population growth and expanded development in Florida, a state that sits an average of just 100 feet above sea level, are coming directly into conflict with accelerating risks from hurricanes and sea-level rise. You could say this is being caused by the increasingly evident effects of climate change—and you would be right—but that isn't the whole story. It's bigger than that.

It's not just that banks handing out mortgages aren't adequately taking on board climate risks predicted for 2050 in Florida. It's also true that, for years, banks haven't been pricing in long term climate risks we've known about. There are homeowners in Pinellas County right now who didn't know when they bought their houses how much it was going to cost to hold onto them. Some of these homeowners won't be able to stretch to keep going. Some of them will become credit risks. Some of them will walk away when they learn they can't sell their house. Banks weren't required to consider these long term insurance/climate credit risks when they wrote their loans. It was in their interest to get the loan written and then sell it on, transfer the risk, to the secondary market.

Today ever-more-complicated derivative instruments that people don't quite understand contain these hidden mortgage credit risks. (Sound familiar?) Meanwhile, homeowners are stuck with sinking home values and sodden communities.

It is not in the state's interest to exit the economic-growth race and recognize these structural problems. Florida does see the structural problem of insurance, but rather than responding "let's reduce the risk," the state's answer is "let's make sure everyone believes we've got a functioning home insurance market."

Although it would be better to act decisively to change how people live in Florida sooner rather than later, the State of Florida—with its closely-linked real estate, financial development, and property management industry—is not going to lead the way. David Lyons, writing for the South Florida Sun Sentinel, quotes one industry representative after another saying that nothing much will change following the storms. Maybe people who want out or can't afford to rebuild will clear out, they say. And then the demand will come roaring back. In rich areas, everyone will rebuild. It's a piece for the ages.

One local banker quoted by Lyons says "I don't have a lot of [borrowers] saying, I don't want to live on the ocean.’ “Most of the people who live in new construction say, ‘fine, bring it on.’”

Governor Ron DeSantis was asked at a post-Milton news conference in St. Petersburg whether there had been "a discussion about not letting some people rebuild." DeSantis acknowledged that storms keep slamming into Florida. "It is tough when you have two back-to-back storms," he said, speaking of Hurricanes Helene and Milton. He went on to talk about damage from Hurricanes Ian (2022) and Idalia (2023).

But then DeSantis pivoted. He leaned into his message, speaking vehemently into the microphone, a collapsed crane in the background:

"So I think that there's always going to be a demand to live in a beautiful part of the world.

"Maybe I took it for granted growing up around here, but you can go all across this country and not find beaches better than what you have right here in Pinellas County. The reality is, is people work their whole lives to be able to live in environments that are really, really nice and they have the right to make those decisions with their property as they see fit. It is not the role of government to forbid them or to force them to dispose or utilize their property in a way that they do not think is best for them."

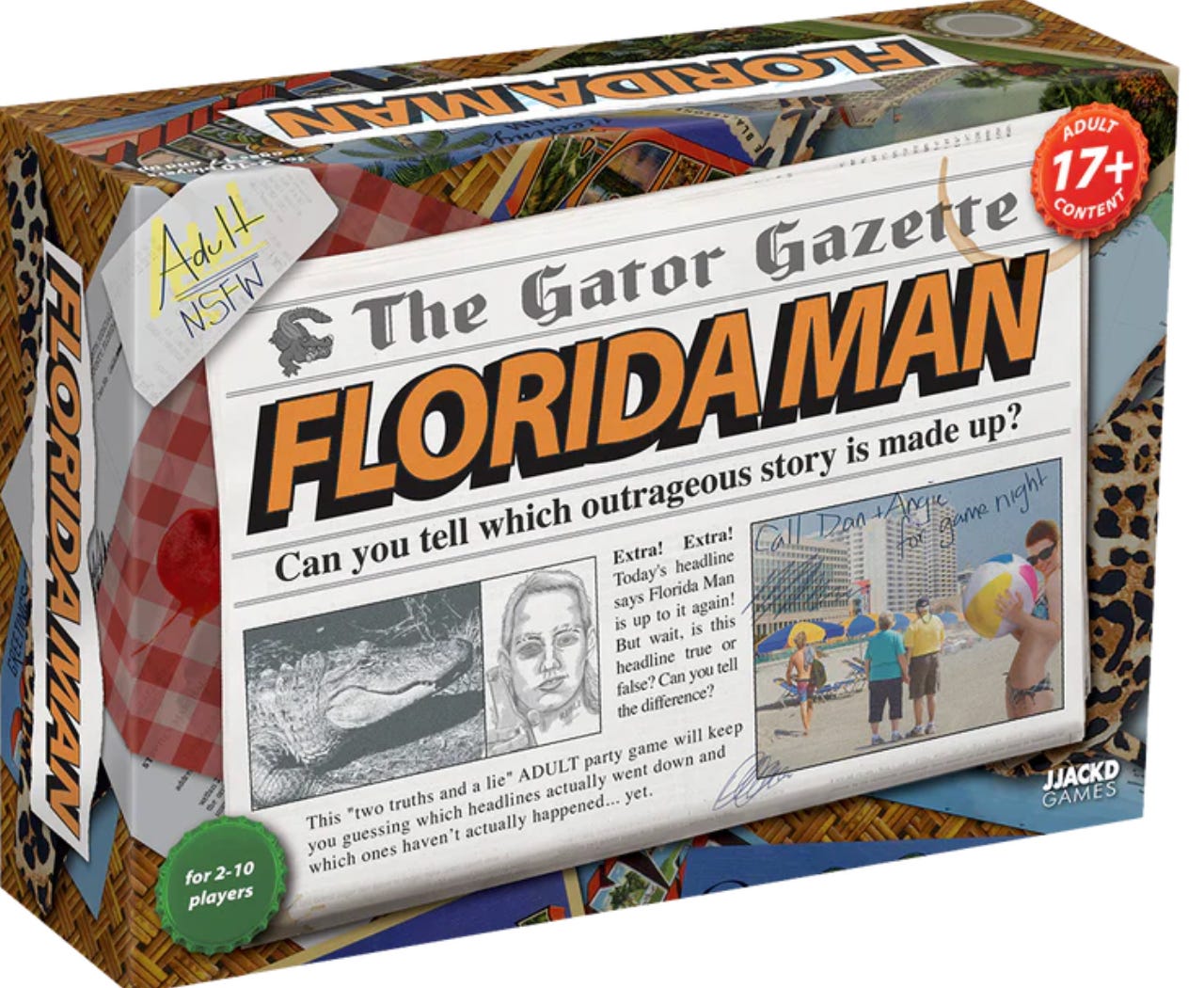

And that, at 33:25, is Florida Man in a nutshell.

Your post are endlessly fascinating. As an ex-actuary, I’ve been waiting for insurers to flee from climate change wreckage areas and I’ve bemoaned the slowness of the inevitable changes. Your clear-eyed reportage and analysis will be a case study one day.

Indeed. DeSsntis doesn’t mention that the government is involved since it backs the insurer if last resort. The climate denial is nothing more than a business strategy after all. In that sense I don’t blame him. But only in that sense.