How to change primitive minds

Making climate adaptation rewarding

We here in Washington, DC just went through a thoroughly creepy run of 80-degree-plus days. Sweltering afternoons, 20 degrees above normal. Although we're now settling into a solid cold snap, along with most of the rest of the Lower 48, the oppressive warmth of the weekend provides a useful physical set-up for considering this question: Why don't more public leaders take action on large-scale adaptation?

It's not impossible. Some leaders are already doing this. The Commonwealth of Massachusetts just released a report saying that up to 4.2 feet of sea level rise above 2000 levels is expected by 2070, and that "The combination of sea level rise and increased levels of precipitation will likely result in the increase of duration, intensity, and frequency of both tidal and storm-related flooding." The report includes a map showing areas of the state where significant numbers of homes will be damaged by the combined effects of sea level rise, tides, and storm surges in 2070. Notice Martha's Vineyard:

The plan is full of calls for cross-government collaboration aimed at addressing inland as well as coastal flooding, and even mentions "explor[ing] managed retreat."

Jacksonville FL just released a pretty brave plan called Resilient Jacksonville (h/t Mark Neville) that similarly acknowledges the importance of "planning for targeted relocation before a crisis occurs" and mentions the need to relocate critical assets (including utilities). Jacksonville's language is strong:

Soon, many homeowners may be facing financial stress from rising homeowner’s insurance costs or even loss of coverage. Renters may be subject to decisions out of their control.

Streamlining and strengthening assistance programs in flood-prone areas can increase residents’ understanding of their existing and future risks and provide meaningful options and agency in the decisions they make about their future. This includes resources to make retrofits and upgrades and creating pathways to relocation that respect residents’ economic conditions, social networks, and cultural preferences.

As Amy Boyd Rabin told the Boston Globe with respect to the Massachusetts plan, "What really counts is what gets implemented, not just planned," but at least these places are looking ahead to 2070 and talking about what needs to happen.

What will it take to change the facts on the ground? I'm interested in figuring out what legal and financial systems stand in the way of dignified, well-thought-out "pathways to relocation" and what changes peoples' minds about the urgency of action. The Biden administration has taken a huge step in supporting climate spending through the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and the Inflation Reduction Act, but most of those provisions center on reducing emissions. A comparatively small amount of money is pointed toward adaptation. (To be sure, the administration has put more money into its Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities program (BRIC), a competitive process that is hugely oversubscribed.) What would it take to encourage the administration to do more in more places with wider effects?

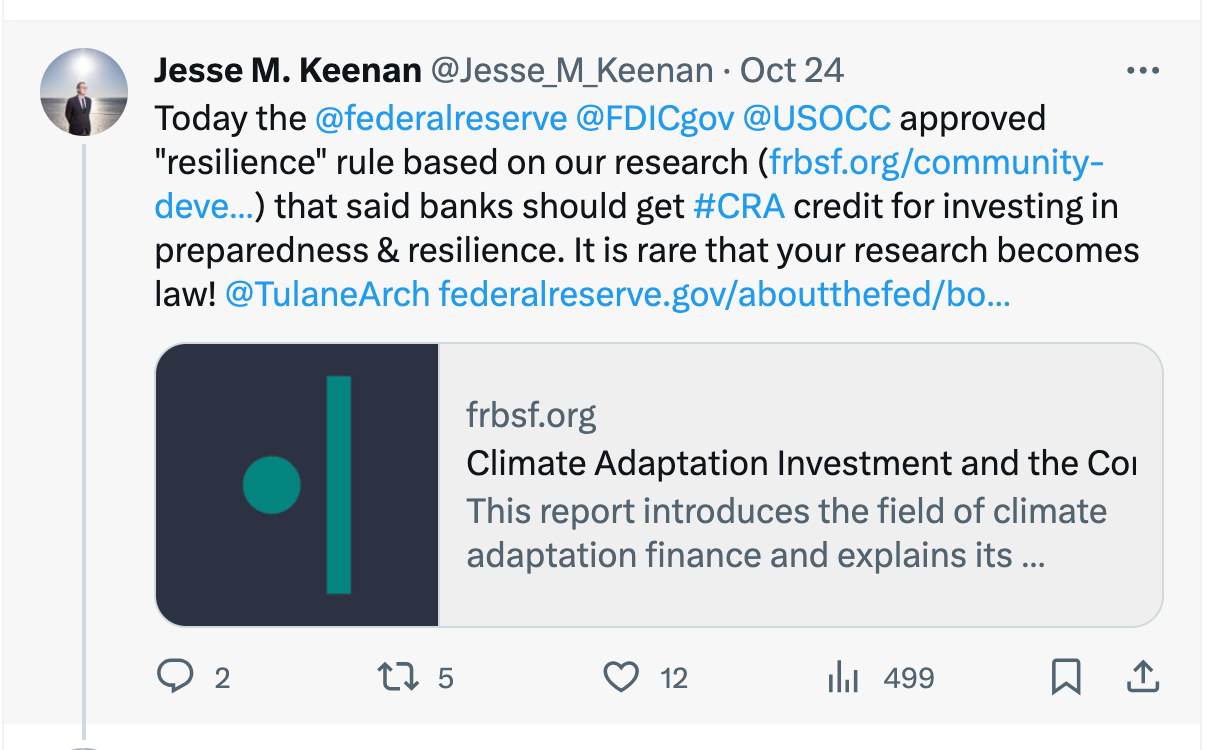

Financial minds will say that when investments are systemically affected, attitudes toward relocation policies will change—because investors will demand that they change. The same day the FDIC released its guidance for banks recommending that they manage their climate risks, the Federal Reserve, the FDIC, and the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency released rules under the Community Reinvestment Act that offer banks incentives to help low-income communities prepare for the consequences of a heating globe. (Relocation is included, as long as it is not forced or involuntary.)

This is a big deal. Bank regulators are providing good reasons for banks to invest in their communities' adaptation needs. Jesse Keenan has been working on this issue for years.

(Read Keenan's 2019 report for the SF Fed about this—it's terrific.) Investors will notice these shifts (along with the increased physical climate risk disclosures the FDIC is requiring), and some will want policymakers to plan ahead more broadly for adaptation. Then things may start to change quickly.

Ultimately, to change minds we need to remember what those minds have in common. I've been quite taken this week by Minding the Climate, a book by pediatric neurosurgeon Dr. Ann-Christine Duhaime. (I know Dr. Duhaime slightly and admire her.) Dr. Duhaime vividly describes what is known about how our brains evolved and what effects this inherited history may have on our behavior and our ability to change our ways in response to climate change.

I particularly loved her description of the timeline of human evolution as the equivalent of a walk across the US that takes 40 days and ends in Times Square. That history starts with the formation of Earth in San Francisco; life emerging in Salt Lake City 30 days ago; multicellular organisms showing up in Iowa City, IA with just 13 days to spare; mammals emerging in Scranton PA 41.5 hours from the end; primates arriving with 13.5 hours to go; and humans showing up 2.5 minutes before the end of the journey. We just got here. It took a long time for natural selection to do the pruning that resulted in our brains. And the Anthropocene, the arrival of human-caused climate change, began just as "the big toe hits the ground during the last step, or the last 0.18 seconds, of the forty-day walk."

Our brains' reward systems are deeply embedded, built with equipment that evolved over millions of years, and they aren't changing as quickly as the climate is. On the whole, we choose to do what we do because we find it rewarding, because microscopic spritzes of dopamine are bathing gazillions of signals and inputs and connections, because we are subconsciously weighing uncountable influences and finding one set of choices preferable. Short-term rewards deeply affect our choices, and money has great meaning to modern humans as a secondary signal of survival, of food and comfort. We feel particularly rewarded (even if this is irrational) when we get more money than we were expecting or when we feel we are doing well compared to others. No wonder campaign contributions have such influence on politicians. JK.

The task is to make the systemic behavior changes needed for adaptation rewarding. And although what we find rewarding can change—thank goodness for plasticity and learning—money will remain salient. That's why it's a good idea to encourage investors to care about adaptation. Politicians will notice that signal. Luckily, we’re also rewarded by unselfish behavior and designed to cooperate by behaving fairly and sharing resources, particularly when times are tough. Or so we hope.

The heat island effect is also a strong issue for cities as these deserts of concrete retain so much heat. Medellín is a great example of climate adaptation with its green corridors that allowed the city to cool down on average by a staggering 2 degrees Celsius. On this front, however, I am not sure financial incentives are a solution where public investment in green infrastructure is more needed. Even the market is reacting to climate change as I have seen real estate developers using temperature heatmaps of the city to buy buildings around parks in Zürich because they were coolers in Summer.