It Never Rains in Southern California

And other projections into the future

It's been more than 50 years since my family moved to Southern California, but I vividly remember the resentment directed toward succulent plants by my mother, an East Coast gardener. They don't need water, those fleshy stolid things, and so she despised them; she missed seasons, and rainfall, and Robert Frost poetry.

She wouldn't recognize Los Angeles today, as life-threatening rainfall pummels the city. This is the first time the LA metro area has ever been under a "high risk" warning for flash flooding caused by rainfall.

It's a dangerous, uncanny day there, as an atmospheric river of wet air hundreds of miles wide traveling in from Hawaii is amped up by the warm ocean, hits the mountains lining the area, and dumps its payload on the heads and houses of tens of millions of people.

That’s why, notwithstanding the intervening decades, Allen Hammond's song about an aspiring actor or songwriter who has a run of bad luck in Southern California is running through my head. Here's the melancholy chorus:

Seems it never rains in southern California

Seems I've often heard that kind of talk before

It never rains in California, but girl don't they warn ya

It pours, man it pours

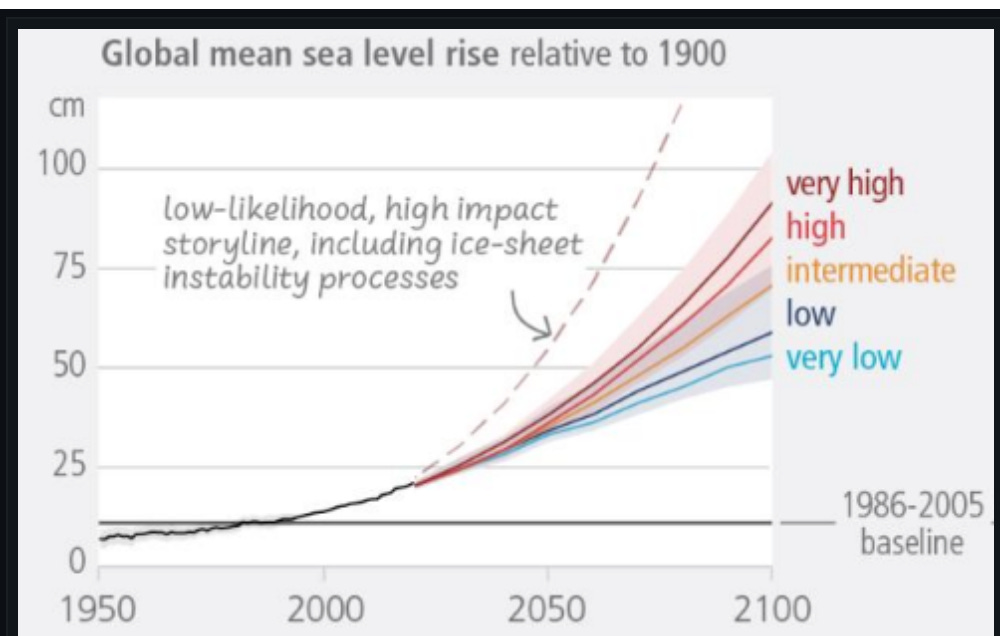

Speaking of misleading talk about weather: In the adaptation world, there's an awful lot of talk about what amount of sea level rise is ahead in 2050, 2070, or 2100. People haul out charts full of smoothly-drawn curves and say, essentially, "The cataclysm isn't coming for decades. We have time to plan. We'll engineer our way out of this." Here's one:

The rapid acceleration in sea level rise doesn't seem to arrive until around 2050 or 2060. So even though we already know that seas are now rising three times as fast as they did in the 20th century, it still seems as if there's time to plan before things really move quickly. Twenty-five years!

But these are average numbers, as Dr. Andrea Dutton of the University of Wisconsin-Madison testified last month. Starting now, people along the coasts will be experiencing ever-more-frequent flooding caused by greater amounts of water. So they'll experience sea levels of say two feet higher than they were in 1900 once or a few times a year initially, then later a dozen times a year, and then more often until that average overall value of two feet of sea-level rise is reached. There will be a continuing series of uncomfortable events, until the discomfort becomes too much to bear. "The tolerance for sea level hitting that point will come much sooner than is implied" by the curve, Dutton pointed out.

This is a fundamental problem. Averages and consensus values play major roles in planning these days, even though we know from geologic history that there can be sudden jumps in sea levels as polar ice sheets deteriorate. We also know that warming is happening now a hundred times faster than during the natural ice age cycles of the past. So there could be very sudden jumps sooner than we think—say a foot or more a decade, as happened 11,000 years ago. Here's Dr. Dutton again:

Sea-level rise projections have been developed according to different carbon emission scenarios to help us understand the probable response of sea level... These are useful for planning, but reliance on the most probable or central estimate outcome masks the true risk in what is referred to as the long tail. Long-tailed (skewed) distributions have uncertainties that are unequally distributed around the central estimate. In the case of sea-level rise (and many other climate impacts) this means that the central estimate more likely greatly underestimates the true risk rather than overestimates it.

Watch out for those long, thick tails. They should be warnin' ya.