It's tough to be Tim Lenton

Meet the climate scientist trying to get policymakers to understand the nonlinear, catastrophic changes just ahead

The idea that a small change can make a big difference to a stable system, eventually causing it to jump suddenly into a different state, is powerful. Tim Lenton of the University of Exeter https://geography.exeter.ac.uk/staff/?web_id=Timothy_Lenton has been talking about this idea in the context of climate change for the last 15 years.

Over the last week, he led a group of hundreds of climate scientists in releasing a new Global Tipping Points report.

The news is that several key elements of the earth's system are already sending signals that they are about to move abruptly into different states that will be difficult or impossible to reverse on any human-relatable timescale. To appeal to readers looking for good news, the Tipping Points report harnesses the same set of ideas about nonlinear dynamics to suggest that there are "good" systemic changes humans and markets could drive in response, like government actions propelling exponential uptake of renewable energy and electric vehicles around the globe.

It's hard to make news on the climate front, and Lenton's cause wasn't helped by Princeton climate scientist Michael Oppenheimer, who told Nature he was "skeptical" that focusing on large-scale climate disasters would trigger action when it comes to lowering emissions. Oppenheimer suspects, reasonably, that increasingly frequent extreme weather events are more likely to change minds. He'd like to see governments taking action in the first place to "turn around the supertanker of global emissions of greenhouse gases."

Both of these two are in the business of being scientists who are also public intellectuals, and from this layperson's perspective the bad news portion of Lenton's report is truly interesting. It should make residents of cities along the Atlantic coast of the US demand coordinated action.

Once you learn about complex adaptive systems, you start seeing them everywhere. Lenton's insight is that there are climate systems, like the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation, that have basically been at equilibrium for the last several thousand years—there are fluctuations now and then, but they're answered by dampening feedback mechanisms that nudge the system back toward its "basin of attraction," or its status quo stable state. The West Antarctic Ice Sheet is another such system.

Applying heat of various kinds to these systems "forces" them to change at the same time that the dampening feedback elements of those systems become weaker. The variance in these fluctuations increases in amplitude (a big wobble) and fluctuations become more persistent. The system is signaling destabilization or loss of resilience, in that it just can't get back to its status quo as easily or quickly. And then, suddenly, amplifying feedback gets so strong that it takes over and self-propels change in the system. These changes will continue even if the forcing is removed. The system goes through a sudden phase change or regime change, jumping to a new steady state--that's the non-linear reorganization that Lenton is talking about.

Two things struck me about Lenton's current report. One is that systems have different steady states to choose from, in effect, and paleoclimatologists have a lot of evidence that the earth has sampled several other steady states over its history. Several other "basins of attraction." There seem to have been very abrupt phase changes between many of them, based on ice core evidence. This tipping could happen again, over a few decades. (Lenton says that episodes of past abrupt climate change have been coupled with abrupt changes in early societies. The next wars may be fought over water.)

The second thing that struck me was Lenton's wry comment that "Each time the IPCC has reassessed the likelihood of what it used to call large-scale discontinuities in the climate system, or 'tipping points' for short, it's lowered the temperature at which they become a risk." Take a look at this:

The risks of major climate elements changing all at once keep getting higher, in other words, according to a huge group of the world's scientists.

According to Lenton, we're now (at 1.1º or 1.2º above pre-industrial levels) already at a moderate risk of seeing the ice sheets of West Antarctica pass tipping points. At 2º, which is where we'll be before the end of the century, he thinks the "irreversible collapse of Greenland and West Antarctica is likely to become locked in." He says we're already seeing warning signals that are consistent with the AMOC heading towards a tipping point and a slowdown.

And, he says, "these are tipping points that pose threats of a magnitude that has never been faced before by humanity," such as a widespread loss of capacity to grow major staple crops. "To me," says Lenton, "it's amazing how little research overall is being done on the impacts of passing tipping points." He and his colleagues are calling on the UN Secretary General to convene a global summit on these tipping points, because the stability of all of our human systems is tightly coupled to the stability of our current earth systems.

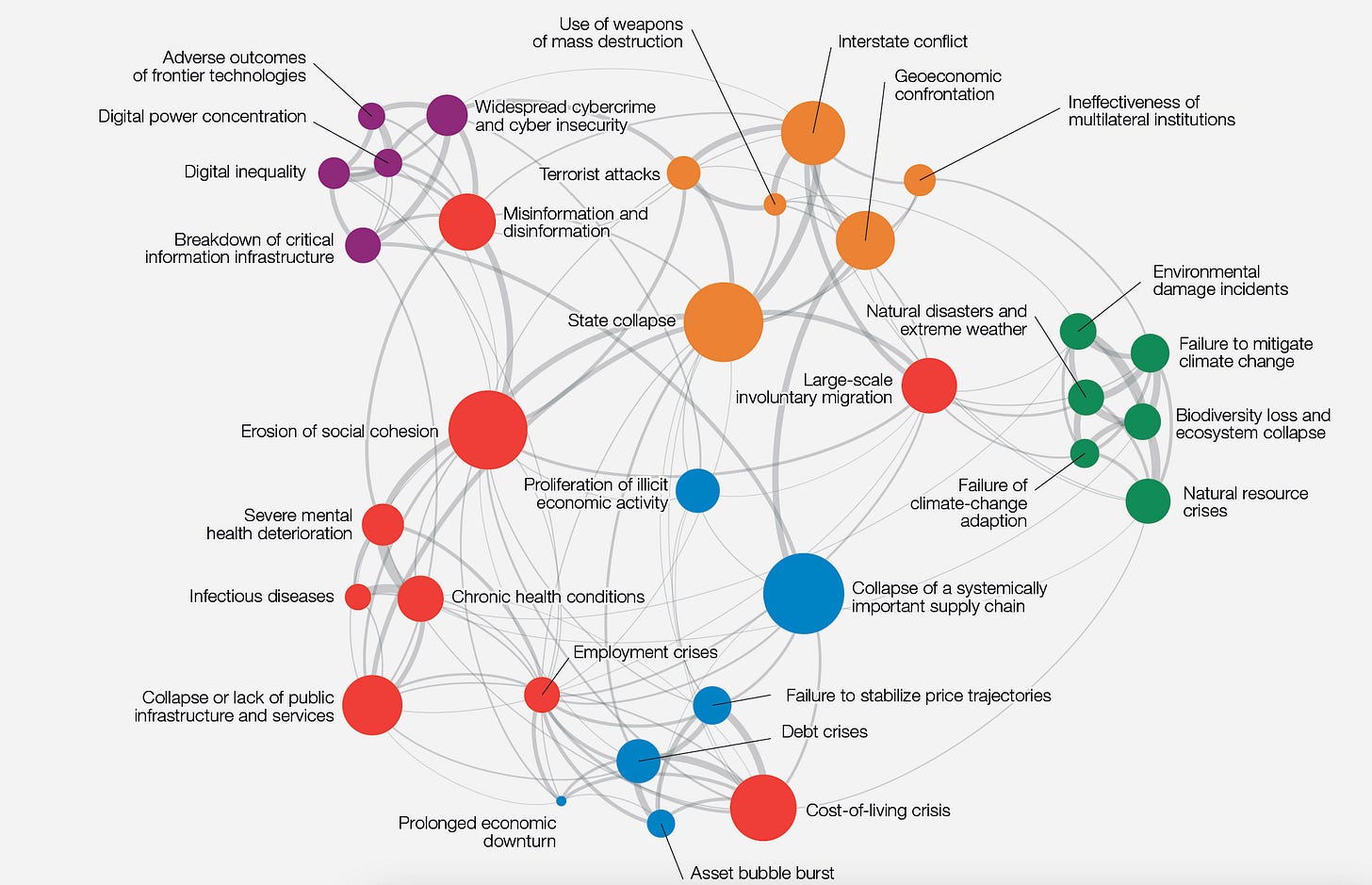

The "and social/governance systems can change too!" part is less convincing. I know Lenton and his colleagues are trying to provide hope and encouragement. But in a 2022 talk Lenton noted that environmental risks are treated as something of a side matter by world opinion. Take a look at this picture from the 2023 Global Risk Report of the World Economic Forum—zoom into the image:

There's the climate, over on the side, very weakly connected to the rest of the network of risks the world faces. "So I feel like we still have some work to do in this transdisciplinary sense to explain to everybody how fundamental tipping points in the green stuff could be for the rest of the stuff," says Lenton.

He's right, of course. And he may be onto a basic communications strategy: "stuff" is easily understood. Stuff is about to change dramatically.