Las Vegas is heating up faster than almost every other American city

So why doesn't Nevada have heat illness prevention rules on its books?

I'm going out to Las Vegas tomorrow for work. It's likely to be hot: Temperatures there have gone up by about 3ºF over the last 20 years, and the city is heating faster than almost any other city in the country. Here's a chart showing the average July in Las Vegas since 1949.

The state as a whole has relatively high climate vulnerability: extreme heat, droughts, wildfires, water availability issues.

Not a lot of billion-dollar disasters have hit Nevada. It suffers about 1.2 billion in damages from extreme weather events a year, mostly in the form of droughts, wildfires, and (in 2021) a winter storm.

Still, the heat is climbing, and that's chronically dangerous for outdoor workers. Lethal.

Here's a word I didn't know: Rhabdomyolysis. That's one of the many things that can happen to people working in extremely hot conditions. Your muscle tissue basically melts under the strain of keeping your body temperature at a safe level, and releases dangerous proteins into your bloodstream. (Nickname: "Rhabdo.")

The human body cannot "adapt" fully to prolonged extreme heat conditions, and neither your state of fitness nor your devotion to guzzling water will save you. (Read Jeff Goodell's terrific book, "The Heat Will Kill You First.) If your body gets too hot too fast, you are in big trouble.

Your heart will race to move blood toward your skin so that it can be cooled by sweat, but eventually (unless you quickly cool down your core) you will be generating heat faster than your body can dissipate it, and things will start to give way internally. Your cells balloon, proteins are deformed, and your organs fail. The theoretical limit of what humans can endure is about 113ºF with 50 percent humidity or about 102.2ºF with 75 percent humidity.

But you can get sick at lower temperatures. At 87.5ºF wet bulb temperature—a measure that takes into account temperature, humidity, wind and cloud cover—it's considered risky to do anything that raises your body temperature. The federal government counts anything over 90ºF for several days as extreme heat. It's definitely a good idea to consider that level of heat a trigger for real caution.

It's not just heat stroke and rhabdo that are causes for concern: all kinds of health conditions are exacerbated by exposure to excessive heat. Kidneys fail, hearts give out, asthma kicks in, diabetes accelerates. Productivity lags. Overall health, including mental health, suffers. As an economic matter, extreme heat is a heavy tax on a workforce and the businesses it serves.

Last month, the UN issued a report warning that most of the world's workforce is likely to be subject to extreme heat at some point during their working years. The report calls for additional regulatory protections, and notes that many countries are working on this.

The state of play in the US is not ideal when it comes to worker heat protections. The federal OSHA launched a "National Emphasis Program (NEP) on Outdoor and Indoor Heat-Related Hazards" in April 2022, which allows the agency to target inspections in high-risk industries and areas where worker populations are likely to be vulnerable during heatwaves. It leans on outreach and education, aiming to provide employers with resources and guidance. But it doesn't create new standards, and OSHA probably doesn't have the resources to actually carry out lots of inspections.

It will likely be the states that will do the hard work on worker protection. So far, just a handful of states have adopted rules: Arizona, California, Oregon, Washington, Colorado, Minnesota, and Maryland. But not Nevada. (Florida recently preempted cities from adopting their own heat exposure workplace requirements.)

Not that the Nevada regulators didn't try. In 2022 the Nevada OSHA proposed a heat illness regulation (R053-20) that would have set specific requirements for employers during hot weather, including a 90ºF trigger temperature for mandatory action, and obligations to provide cool water, shaded breaks, and heat illness prevention training. Employers were supposed to let workers stop work when they were showing symptoms of heat illness.

But it died after industry opposition.

It's true that Nevada has a "General Duty" statute on its books that says that every employer must

"Furnish employment and a place of employment which are free from recognized hazards that are causing or are likely to cause death or serious physical harm to his or her employees."

But that's hard to enforce. What's needed are triggers and clear standards, as in Arizona's law:

When the temperature in the work area is more than ninety degrees Fahrenheit, the employer shall provide and maintain at all times while employees are present one or more areas with shade or a climate-controlled environment that are either open to the air or provided with ventilation or cooling.

I understand why businesses don't want this. They don't think that a one-size-fits-all trigger makes sense. They already have a duty to act well. They'll lose money if all their workers just start complaining of the heat. But the human body has limits, and it is morally wrong—not to mention expensive in the long term—to ignore those limits.

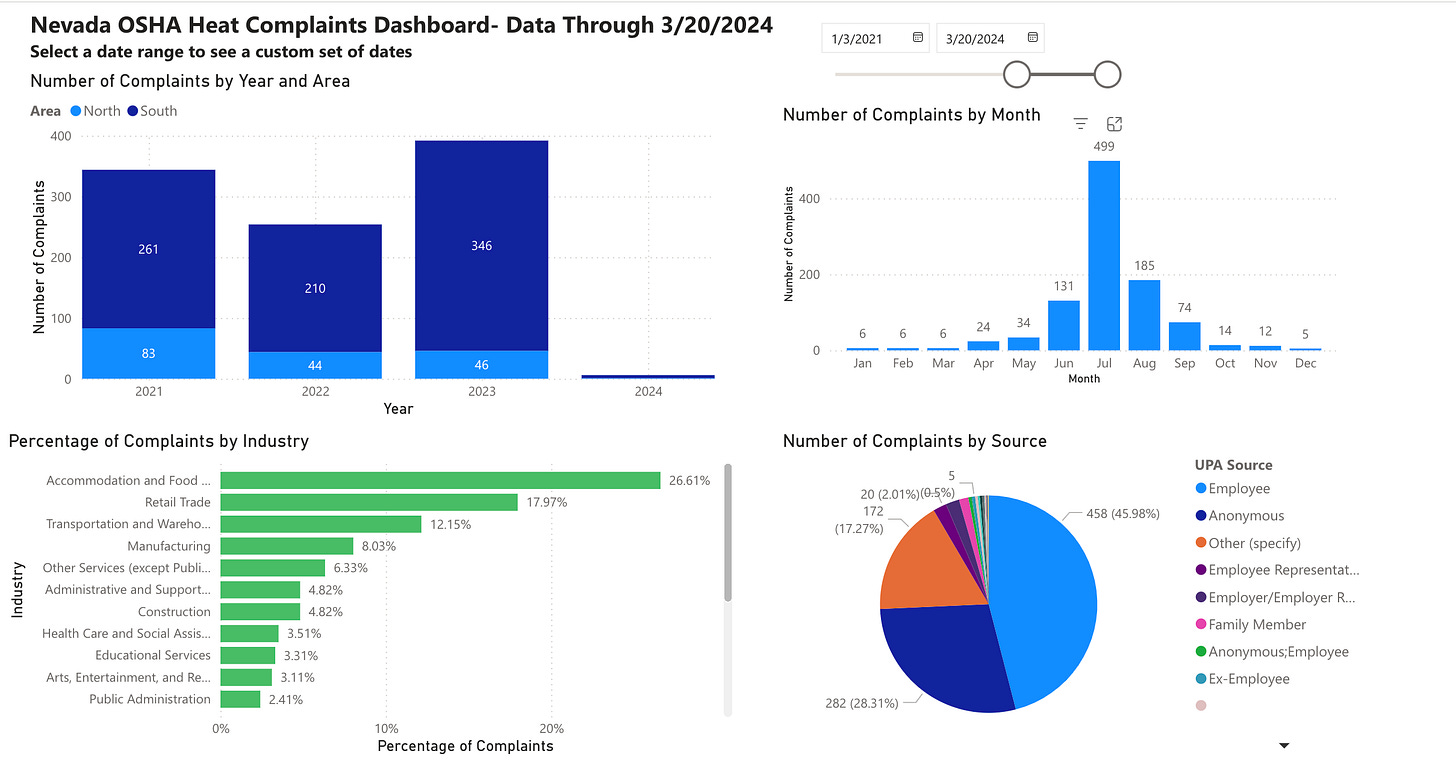

Meanwhile, workers in Las Vegas are complaining—particularly workers in the hospitality and retail industries. The number of heat complaints in Nevada climbed in the brutally hot summer of 2023, and was highest in the southern part of the state, where Las Vegas is.

I hope things will change in Nevada. I'll report back.

Even Bugsy looks warm: