New Jersey is updating its land use requirements to incorporate climate risks

Big changes ahead for investors, developers, homeowners, and municipalities

Of the top five most flood-prone counties in the U.S., four are in New Jersey. Sea level rise is happening in New Jersey more than twice as quickly than the rest of the globe. In Atlantic City, "sunny day" flooding that used to happen less than once a year in the 1950s happened 18 times in 2023. The number of heavy rain events in the state has climbed by nearly 50 percent since 1958. As of 2019, New Jersey ranked third in the nation in claims paid by FEMA, with $5.8 billion going to the state since 1978.

Three years ago, Tropical Storm Ida decimated many inland areas in New Jersey and killed 30 residents. Meanwhile, FEMA's maps of flood risk in New Jersey—the reason people might be required to get flood insurance there—aren't keeping up with reality: over 30% of New Jersey claims following Ida came from places outside FEMA's mapped floodplain. But homes and other assets are still getting built in New Jersey in places that are susceptible to flooding today and are at risk of permanent, daily flooding—chronic inundation—in the future.

Property insurance firms are well aware of the risks New Jersey faces, and double-digit hikes in rates there are common. Now the insurance repricing the state has already seen will likely be joined by repricing in coastal property values: New Jersey is facing reality and planning to change its land use rules in mid-2025.

Listen to this: The Garden State, the home of Tony Soprano, the state that brought us Paramus, Paterson, and Passaic, is leading a paradigm shift that will have major consequences for U.S. coastal properties.

It's taken four years of drafting and endless public consultations and meetings with stakeholders. Now the state's Department of Environmental Protection is on track to adopt its "Reform to Support Resilient Environments and Landscapes" (REAL) rules.

They'll be adjusting their flood zones to account for rising sea levels and storm surge, which will mean the first floors of new or redeveloped homes will have to be five feet higher than required today. They're creating an "inundation risk zone" covering homes and other assets that are at risk of being underwater every day in 2100. Builders of new homes in these zones will have to do thorough assessments of the risks involved, build in ways that lower those risks, and ensure that any buyer knows exactly what they're getting into. (New Jersey already passed a general flood disclosure law last year ensuring that renters and buyers know the risks they face.)

All of this is based on current, conservative, scientific projections. As Rutgers University Distinguished Professor of Atmospheric Science Anthony Broccoli testified last month, pointing to a 2019 New Jersey Science and Technical Advisory Panel report, "in a moderate emissions scenario, the likely range of sea level rise in 2100 is expected to be 2.0 to 5.1 feet."

So the rule doesn't assume a high emissions scenario, even though high emissions are being observed these days, but does adopt a risk assessment approach by picking the high value in that likely range—five feet—and using it to protect communities throughout the state. The state expects that homes and roads being built now in New Jersey will still be in use in 2100, and the state believes they should be safe.

The moderate range represented by this projection fits with NOAA's 2022 estimates for the East Coast. As the science changes, New Jersey is saying it will follow. "Every time that the data is updated, it always goes in one direction," New Jersey's State Floodplain Administrator Vince Mazzei said in an online session about the rule earlier this year. "It gets worse. And that's why we want to make sure that we're as high as we need to be." "We are not 'adopting' five feet of sea level rise," said NJDEP's Chief Strategy Officer Katrina Angarone during the same session. "That is what the scientists say is coming."

(From NorthJersey.com)

They're adopting a consistent, statewide sea level rise standard. It’s a major step, and one that puts property markets up and down the coast on notice.

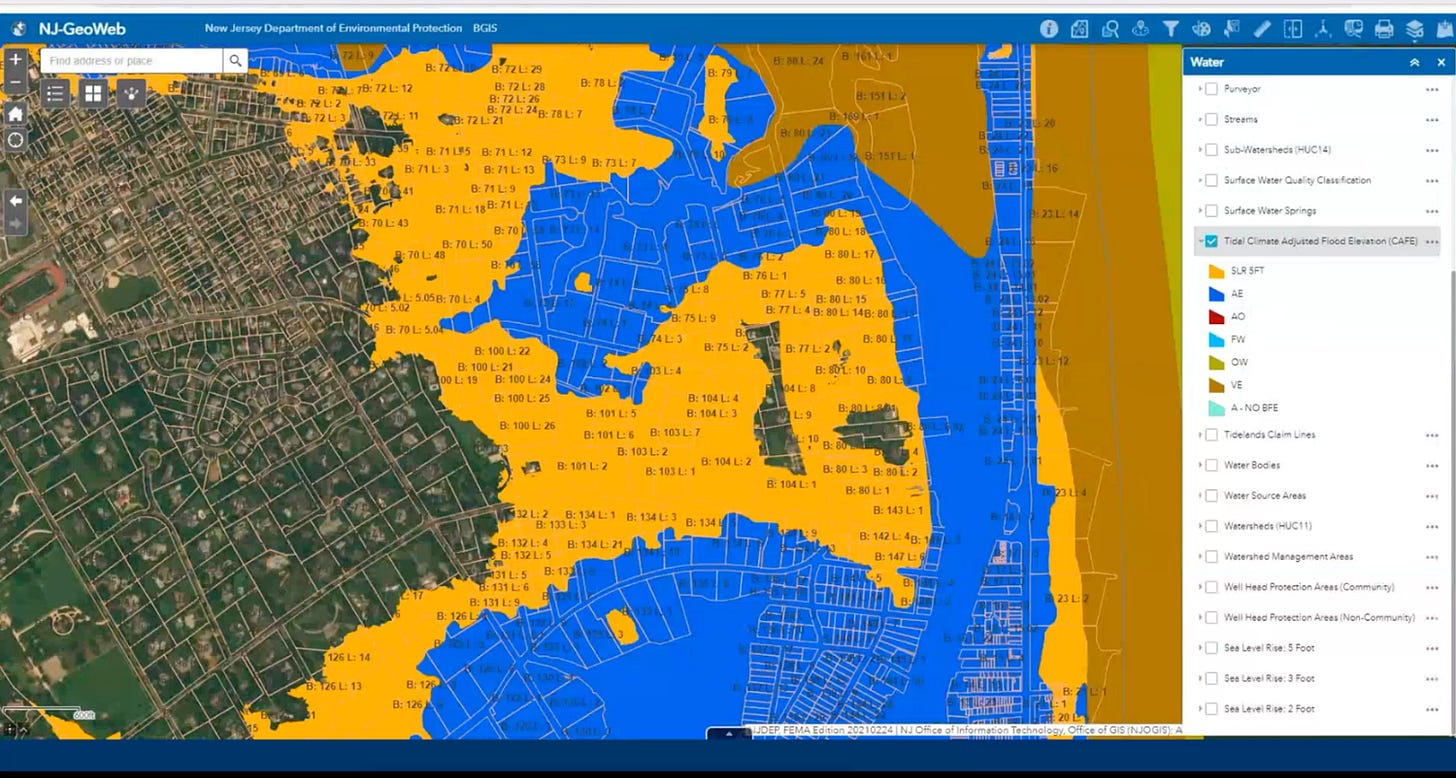

(NJDEP image.) The "Climate Adjusted Flood Elevation" (CAFE) is the increased flood zone in the new REAL rule—FEMA plus five feet. The rule will require new/reconstructed/improved residential buildings to have first floors that are at CAFE plus one foot elevation. Commercial buildings can be elevated or floodproofed or both.

The New Jersey shoreline is a crowded place. The DEP estimates that about 94 percent of the land in the inundation risk zone—the places that will likely be underwater once or twice a day by 2100—are either already developed or are difficult to develop because they are coastal wetlands or are otherwise encumbered. So most of the activity that will be affected by that part of the rule, which requires heavy-duty assessments and engineering work as a condition of permitting, will be redevelopment.

That could discourage investment in these areas, which may also depress property values there as institutional investors wake up. As Carol Ryan reported yesterday in The Wall Street Journal (behind the paywall), "Powerful property investors aren't paying close attention" to how climate changes might affect property values in the future.

Shore counties in New Jersey have particularly high percentages of institutional landlords—twice as high or more than other parts of the state. In fact, the Jersey Shore, like Florida, is a place where calamitous weather and speculative property ownership are colliding.

This is a NJDEP chart of Seabright, NJ. The current FEMA mapped flood zone is in blue. The orange area next to it is the climate adjusted flood elevation area: FEMA plus five feet. Walking surfaces of any residential projects built after the rule within the orange zone will have to be at least one foot above CAFE. The expanded flood zone in the new rule will add about 1.5 percent more of New Jersey's land area into the regulatory floodplain, for a total of about 17.5 percent of the state.

On the political side of things, Cape May County is leading a tussle over the new rule, with Cape May Mayor Zack Mullock asserting at a meeting this week (paywall) that an 80-year-old resident would not be able to replace a roof and windows without triggering the elevation rule. (The rule excepts from its standards repair and maintenance activities that don't alter a building's height, footprint, or habitable area.) According to Bill Barlow of the Press of Atlantic City, "All 16 of Cape May County’s municipalities have approved resolutions opposing the rules, encouraged by a county effort to present the rules as radical and harmful to working families."

We'll hear more from New Jersey. But the effects of rapidly accelerating climate change will clearly be felt in property markets there. State officials are following the science and acknowledging the risks.

Also: there are coastal storm warnings along the Jersey Shore this weekend.