Vertiginous rate hikes in property insurance coming

Reinsurance is dramatic stuff

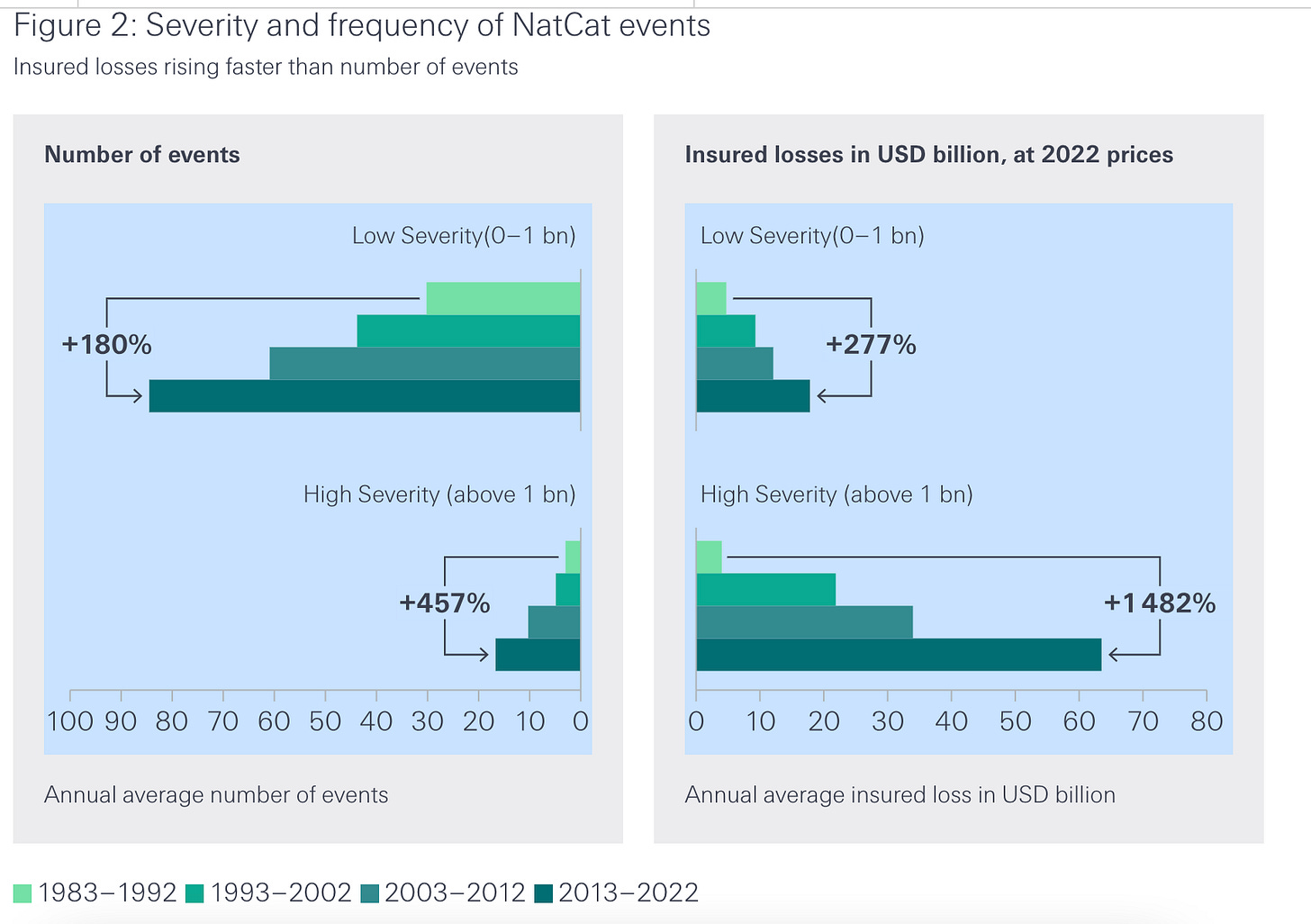

From SwissRe May 2023 online report - more catastrophic events, but EVEN more losses

Although the almost $4 trillion market in muni bonds apparently hasn't yet seen city credit ratings downgraded to reflect climate risks, there are credit rating alarms sounding in the insurance sector. The change ahead is likely to happen very quickly over the next year—more like a helicopter taking off vertically into the sky than the slow climb of a 747. To carry the metaphor further, those helicopters may be vanishing altogether, as additional insurers exit additional markets. Then what?

In the game of musical chairs that is risky real estate, many homeowners who can afford it do their best to shift their risk of catastrophe to private insurers. The cost of that shift is climbing quickly: Average rates for homeowners insurance in Florida went up more than 40 percent between 2022 and 2023, for example, and Floridians pay yearly premiums of almost $8,000 on average. And it's not just Florida and hurricanes. As the Washington Post reports, "In California, worsening wildfires have also driven insurers from the state or forced them to scale back policies. Residents of Washington, Montana and Colorado are watching their coverage options shrink, too."

Insurers, in turn, manage their own risks by sending on some portion of the yearly premiums they receive to reinsurance companies. Reinsurers’ prices are not regulated, unlike primary insurers operating in the US.

The reinsurer assumes up to X amount of the insurer's liability in exchange for Y amount in premium, figuring out each time it signs a contract with an insurer what the ratio of premium needs to be to the losses it may eventually have to pay. There's a term for this: "Rate On Line." Rate on line is that ratio, and when ROL gets higher insurers have to pay more for coverage from a reinsurer. The reinsurer, in turn, can pool its risks globally, banking that it will make a profit overall because not all its risks of having to pay off local insurers will be dependent or tightly correlated.

How do reinsurers figure out what ROL ratio to charge particular insurers? Well, they look in part to agencies that rate risks for them. Last year, Moody's bought a company called RMS for about $2 billion. RMS is, according to the press release that came out at the time it was folded into Moody’s, "the world's leading provider of climate and disaster risk modeling serving the global property and casualty (P&C) insurance and reinsurance industries." You may have thought of Moody's as a company that rates corporate and government debt, but today it's deep into disaster and climate change risk modeling as well.

This past summer, RMS issued a new model for reinsurers to use in assessing North Atlantic catastrophic hurricane risk. According to an industry trade press article, the new model ("Version 23") "points to increases of up to 30 percent in expected losses in Texas, the Gulf, Florida, and Southeast states." The model, among other things, reflects "significant changes" in the amount of development in coastal regions compared to five or 10 years ago.

This means that reinsurers, anticipating that things are about to get much worse for their client insurers, won't want to agree to terms they've signed up for in the past. They'll want much higher ROL ratios. They'll want much more in premium from insurers before agreeing to share those insurers' risks. The inevitable result is that insurers, facing a concentrated catastrophe reinsurance market, increasingly won't have places where they can shift or share risks. They'll, quite rationally, be exiting even more markets that don't make sense financially for them. Those that stick around will be charging their individual customers much more.

The bottom line is that when it comes to insurance in hurricane-prone areas of the US, risk assessments are essentially downgrading the credit-worthiness of the entire enterprise. Very quickly.

Many reinsurance contracts will be renegotiated over the coming weeks and months, and reinsurers will be able to charge substantially more. As Swiss Re put it in May 2023, "we have seen robust price improvements, increased net retentions, and much tighter terms and conditions." This is the language of a satisfied player: "We can charge more, insurers are clinging to their relationships with us, and we can get whatever contract terms we want." Just follow that power down to the homeowner level, and you'll see more and more homeowners "going bare”—deciding it isn't worth paying the sky-high premiums they'd need to pay to carry insurance, and figuring that somehow the federal government will rescue them if something awful happens.

Nothing about this is malign. Insurers and reinsurers are seeing that the numbers of yearly billion dollar events in the US are soaring. The risks are climbing because extraordinary property value growth and urbanization (those "significant changes" reflected in Version 23) have put more people with potential claims at risk. Here's a chart from SwissRe showing population growth in the area where Hurricane Ian made landfall in 2022, compared to growth in US and in Florida:

How about that? So much growth in risky areas means huge growth (potentially) in insured losses, from a reinsurer's perspective. Investors in reinsurers are not going to want to see their capital deployed to cover increasingly risky insurance contracts. When those contracts come up for renewal, the reinsurers won't want to sign them, or will be drawing blood from insurers to sign up.

The power of disaster insurance is that, when it works, it allows homeowners to bridge the transition between crisis and steady-state. Without it, millions will be in spiraling crisis when disasters hit. It's likely that in the coming months, as Version 23 and models like it are factored into the businesses of insurers and reinsurers, the insurance picture for coastal real estate will become far darker than it is now. Then what?