What happens if climate adaptation goes private?

Volatility ahead for municipal bonds may give us a hint

"If the physical effects of climate change are dramatically accelerating," someone asked me this week, "why aren't the capital markets reflecting this? Shouldn't we be seeing movement to make money off this phenomenon?" Good question. Some signs are visible: Insurance markets are steadily repricing to reflect physical climate risk (WSJ: L.A. Has Big Plans to Rebuild After the Fires. Good Luck Getting Insurance) Houses in Florida aren't selling swiftly and property values in risky areas of the state are declining, at the same time that some claim private equity investors are quietly selling their inventory there.

But there's a larger movement, hidden in plain sight, that may become obvious over the next few months. Right now, states and cities borrow money for infrastructure improvements and rebuilding after natural disasters using municipal bonds. This gives local governments access to relatively cheap capital, because investors pay no federal tax on interest earned and therefore accept lower returns. But if the administration eliminates or caps the tax exemption currently supporting the $4 trillion municipal bond marketplace, the $2 trillion private credit market is ready to step in with loans of its own.

What if funding climate adaptation—improved infrastructure, coastal and riverine protection—was left mostly or entirely to the private sector? What would the consequences of such a move be?

Let's start with the first step, which is the idea of capping or eliminating the tax exemption for interest earned off municipal bonds. This week, the House Ways and Means Committee is considering a host of actions to raise revenue to address the nation's deficit while keeping the 2017 tax cuts in place. One of the items on the table is to cap this exemption at 28 percent. This would mean that investors in tax brackets higher than 28 percent would not get the full benefit of the exemption—they would be able to exclude only 28 percent of their municipal bond interest from federal income tax. If you're in the 37 percent tax bracket (the top marginal rate), the remaining 9 percent of interest would be taxable. You'd be getting a tax credit, essentially, but not the full protection that currently powers the entire muni bond market—made up mostly of higher-income investors who rely on municipal bonds for tax-free income. Historically, because municipal bonds offer tax-free returns, investors have been willing to accept a lower level of interest.

Capping the exemption is not a new idea. The Obama administration suggested the same thing, proposing a 28 percent cap on both muni bond interest and the mortgage interest deduction in 2011, 2012, and 2013. Michael Stegman, then a counselor to the Treasury Secretary for Housing Finance Policy, told the public in March 2013 that "a cap on the income tax exclusion will likely be part of any discussion of broader tax reforms." Following extensive lobbying by state and local government groups, including the National Governors Association, the exemption was left undisturbed.

Now state governors are faced with navigating the new federal administration, in a world in which future FEMA funding for state disaster preparedness and emergency responses is uncertain. (The council the president created nearly two months ago to evaluate FEMA hasn't met yet). In this context, governors aren't saying anything publicly as a group about whether the muni bond tax exemption should stay in place. They're in a tough spot, because the $350 billion the federal government would arguably gain by eliminating the exemption is one of the top ten tax expenditures it has in place now. And there is desperate energy behind the move to find $4.5 trillion to keep the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act in place.

The silence of the state governors is a key factor this week making it more likely that the muni bond tax exemption will be cut back or erased. Another is the enthusiasm of the current presidential administration for shrinking the role of government in any arena in which the private economy could be more active.

Much financial punditry these days is focused on privatization. Mike Wilson, chief US Equity Strategist at Morgan Stanley, told Bloomberg Daybreak earlier this week that the "short term pain" being experienced in the stock market was being caused by "some of the things that we need to do to rebalance the economy, which I think is a good idea," and "could lead to benefits later." Wilson continued:

[The benefits would be] that we we shrink the size of government and that liberates the private economy ultimately via deregulation and [stopping] some of the crowding out that's been going on now for several years. I mean, this is, by the way, that's not a new phenomenon. The government has been growing for the better part of my adult life. And so the fact that we're finally talking about maybe shrinking the government, I'm not really sure who's against that. Because we know that's an inefficient way to allocate capital. And if you can get the private sector doing that job instead, that's the payoff down the road.

So let's play this scene out. If the tax deduction is reduced or eliminated, municipal bond markets will abruptly become volatile as investors exit. That's the message from Municipal Market Analytics, which published research this week suggesting that within three to five days of the introduction of a 28 percent cap there would be a sharp drop of between 4.5 and 7 percent in the value of a 10-year, 5 percent coupon, high-quality municipal bond because of both reduced tax benefits and investor uncertainty. Over the entire municipal bond market, this could mean the loss of $200 billion or so in value, as retail investors pull out. In order to attract buyers, municipal issuers will have to offer higher interest payments. There are almost 40,000 issuers in this market, and many of them are tiny (the 29,000 smallest borrowers account for 10 percent of the market). Many may be unable to refinance their debt; many may be unable to meet their interest obligations and will default.

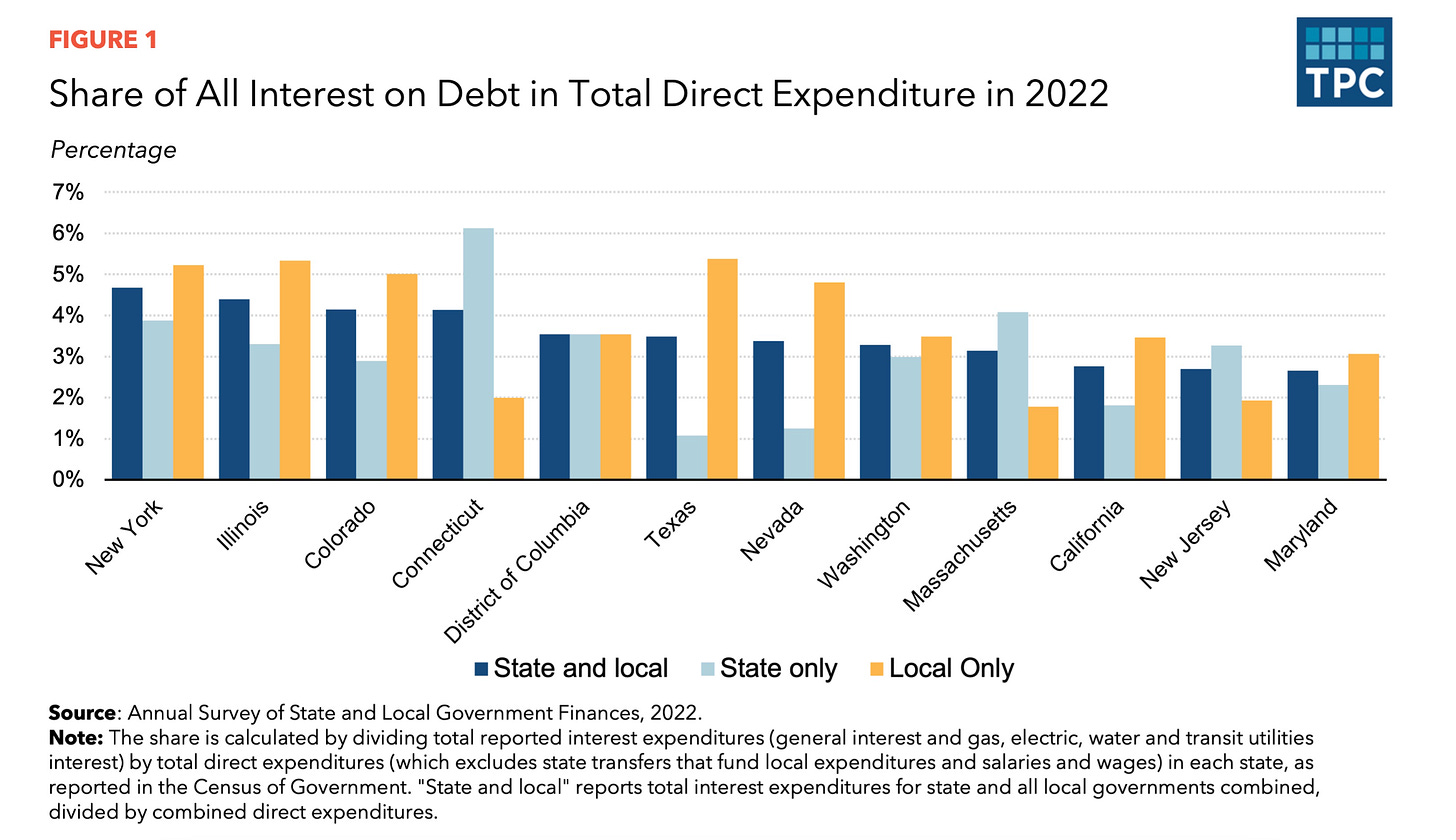

In a world in which, right now, three-quarters of all public infrastructure is publicly financed, this will be an abrupt and likely destructive change for many places. As it is, as of 2022, states like New York, California, Connecticut, and Illinois spent nearly 3 percent of their outgoing funds servicing debt (Brookings Tax Policy Center report here):

But if you're focused on efficiency and capital allocation, maybe you don't care if life suddenly gets much more expensive for New York State (or for cities like Atlanta and Chicago). This will be an opportunity for private capital, pension funds, and others to provide capital to municipalities. At higher rates. Private credit has become a "billionaire factory," according to Bloomberg, with its high yields and steep fees. Why should raising debt for public purposes be treated differently than any other debt market? Yes, some infrastructure may not get built. Smaller, poorer places may not get attention. Ah, but the principle of privatization will be at work.

This vision of the central role of the private sector—driving efficiency at all costs, whatever volatility and despair happens in the short term, particularly for weaker, smaller places—is dominant right now in America. There are longer term considerations that could be part of the conversation, including the exceptional US role in the global economy that historically has been based on its predictability (as well as its reliance on the rule of law), but at the moment these ideas are out of vogue. If this story rolls out as I have described, with a cutback or erasure of the exemption (Obama wanted it, negotiators will say, and no one with power is fighting for it), leading to a stepped-up role for private credit in municipal finance, we may see a focus on infrastructure only for places that can handle the burdens of seeking financing from distant, private partners who have a fiduciary obligation to charge as much as they can for use of their capital.

All of this has major implications for climate adaptation. At the moment, it is the public sector that is the dominant force in America, as around the world, in climate adaptation spending. Private capital may soon be moving to fill the gap. This may interest my questioner from earlier this week but will cause dismay in many other quarters.

I believe that in or around 1970, some of the heads of fossil fuel corporations and possibly others, came to the conclusion that eventually the natural resources upon which their fortunes were based would start to decline and ultimately run out completely. They didn't ask themselves how can we manage this to preserve these resources, or ration extraction and prolong sustainability. They couldn't trust each other not to take advantage and dominate the market. Part of their plan was to reduce oversight, control, and legal interference from public interests as expressed through government. Abolish government, at least the most bothersome aspects, and set corporate America free to maximize and accumulate wealth and power. To the extent that infrastructure is necessary for their interests they will take control. Public needs are irrelevant and will only be met in a way that builds wealth for corporate interests. The idea of government that addresses public needs has been on their chopping block for over 50 years.

If this is off point and irrelevant, my apologies. I don't understand economics and financial issues very well, but I know that privatization of disaster relief is part of the corporate plan to dismantle protection of public interests and to privatize any services offered whether it's flood control or disaster relief.

We keep looking only at traditional models. As Lincoln once said, as our case is a new so we must think a new and act a new. New ways to streamline the flow of private capital to offset the costs of severe weather on communities. There is an innovative new pilot live now in Boston, MA with 5 other communities asking for campaigns. 501c3 nonprofit, private sources of capital, debt-free financing for civic climate resilience: https://www.shovelreadycapital.org/shovel-ready-boston