What is likely to be a stunning hurricane season will rattle housing markets

Loud signals, doubled anomalies, and thickets of correlations

It's hard to pay sustained attention to the shrinking ice masses at the poles, even if you know that ice moving from land to the sea poses unthinkable risks to coastal populations and that ice on land has melted very quickly in the past. It's even hard to focus on flooding, because it comes and goes and is forgotten by people not in its path. But a sustained series of rapidly intensifying storms along the US Atlantic coast, amped up by warmer seas—that might grab mindshare and change risk perceptions, particularly if life in several sizable coastal cities is suddenly and simultaneously disrupted.

Based on what we know about what's ahead this summer, this kind of awakening is likely. When it happens, property markets will inevitably be affected.

In a nutshell, extraordinarily warm waters, weakened wind patterns, slowly-moving large-scale atmospheric phenomena, and naturally-occurring climate fluctuations are all combining to create perfect conditions for a magnificently active Atlantic hurricane season beginning a couple of weeks from now, with more storms tracking toward the US coast. The European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF), known for creating the most accurate models around, is predicting that this will be the most active season in more than thirty years—significantly more active than any other season over that same period. (Follow Dr. Levi Cowan (@TropicalTidbits) as the months pound by. I am indebted to him for many of the images that accompany this post.)

Some of this is unquestionably driven by rapid warming: warmer sea waters provide more energy for storms, which means more rapid intensification of more intense storms, higher wind speeds, and more damage to homes. That rapid warming is also undoubtedly contributing to changes in atmospheric patterns that are also lining up to support these more ferocious storms. But homeowners, insurance companies, and prospective buyers will focus on what happens, whatever its cause. So let's take a swift look at these signals and correlations.

Very hot sea surface temperatures.

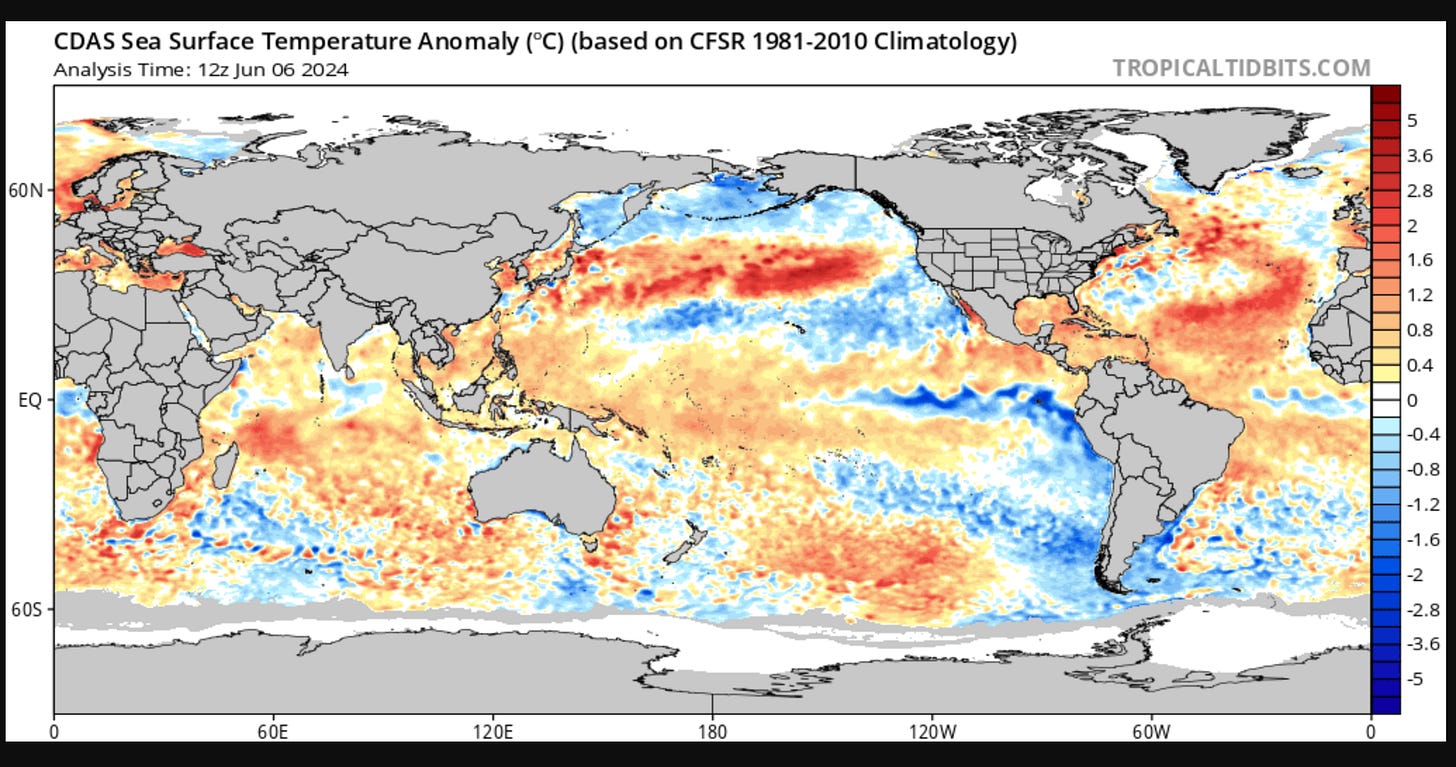

This is the current map showing where the ocean surface water is warmer than usual (in orange and red) and colder than normal (in blue). See the big blue tongue of water spreading out from the west coast of the US? That signals a La Niña pattern in the Eastern Pacific. See the very warm water in the tropical Atlantic? It's hardly ever this warm there. These two things are big, loud ocean signals, and they're forecast to persist through the August/September/October hurricane period (this chart shows a prediction based on multiple climate models):

That warm water in the tropics means the air above it will be warm, humid, and rising, making for a more forceful contrast with cooler air masses. That contrast will create unstable zones that amplify and end up producing those counter-clockwise spirals that are the markers of hurricanes.

Two fundamental wind anomalies will make storm formation easier. Hurricanes are less likely to form in the Atlantic when wind shears—roiling differences in wind speed and/or direction between the lower and upper levels of the atmosphere—interrupt their capacity to rise and cohere. The less wind shear in the Atlantic, the more hurricanes.

Well, two big anomalies are kicking in that are dialing down wind shear quite dramatically: weaker than usual trade winds (blowing from east to west) a mile above the surface of the Atlantic, and weaker than usual westerly winds (blowing from west to east), high up in the atmosphere.* Less conflict, more hurricane formation.

Boatloads of correlations will make storms more likely. There's a strong historic connection between unusually warm sea surface temperatures in the Atlantic and the overall hurricane activity there. There's also an association, although a weaker one, between a warm tropical Atlantic and hurricanes making landfall in the US. That tongue of blue water in the Pacific, the La Niña? It's also correlated with a busy Atlantic hurricane season. And there's a very strong signal that the Pacific La Niña is correlated with more total storm landfalls (all tropical storms) on the continental US.**

Storms will more likely track toward the US this summer. We have just about seen the end of the 2023/24 El Niño event. El Niño is accompanied by a strong subtropical jet stream, high in the atmosphere, that blows from the west to the east. That's been good for steering hurricanes off our Atlantic coast. No longer! During La Niña, that big cool upwelling in the Pacific, the steering will be in the other direction on average. Right toward the coast.

Storms may start arriving in a couple of weeks. Climate scientists pay special attention to the Madden-Julian-Oscillation (MJO). You can think of it as a large region of windy stormy weather that moves slowly to the east from the Indian Ocean over 40-90 days. The more slowly it moves, the more likely it is that there will be even more hurricane activity in the Atlantic once it lands there, because it also reduces wind shear. A few days ago, the Climate Prediction Center said that our friend the ECMWF was predicting that the MJO would be propagating across the Pacific to the Western Hemisphere. It may arrive in the Atlantic during third week of June. This also increases the chance that storms will be born in the Atlantic basin early in the hurricane season.

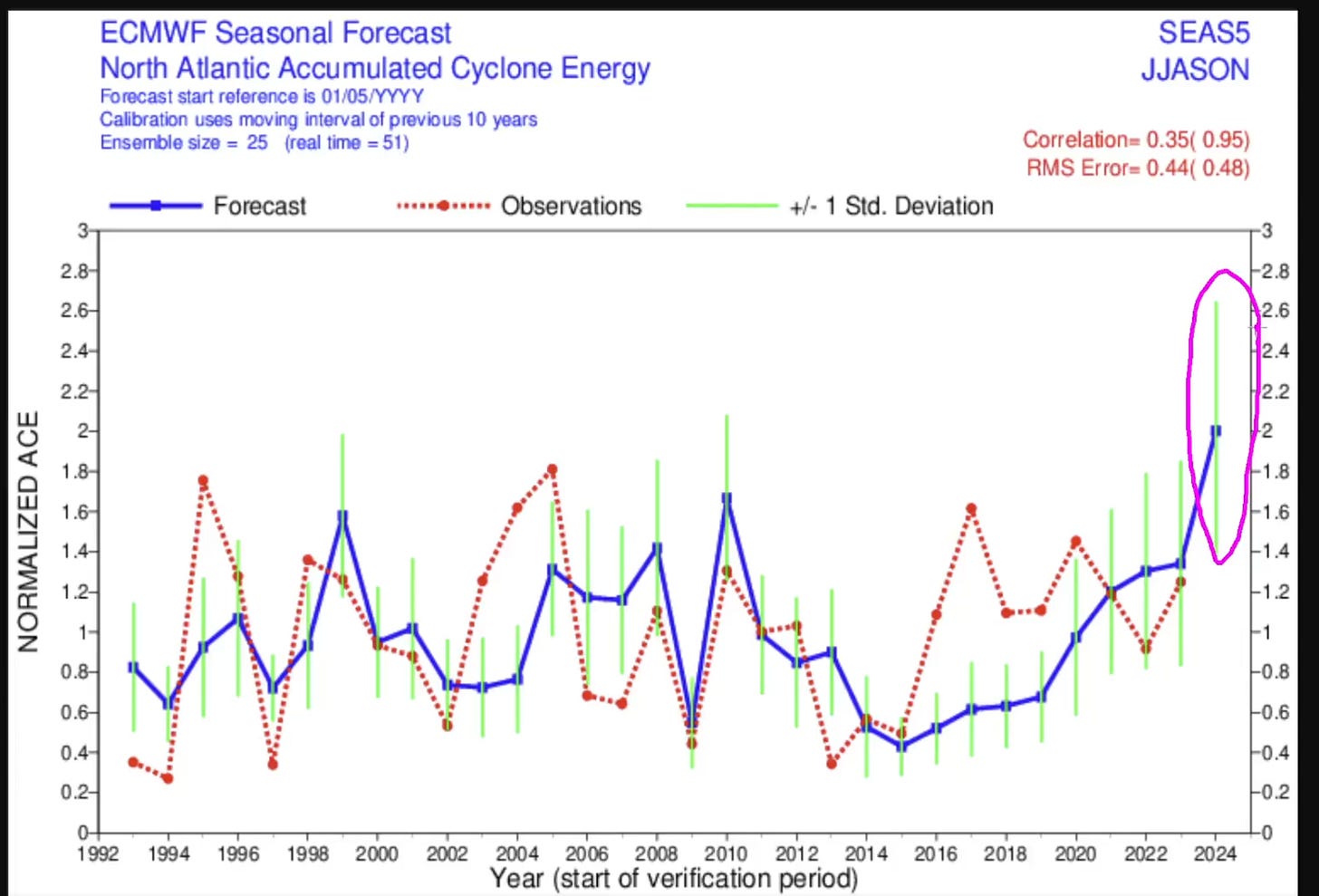

The best model points to a greatly amplified hurricane season in the Atlantic. For all the reasons we've just been through—hotter water, weaker wind conflicts, and historic weather patterns—the climate modelers are predicting that there will be a huge amount of Accumulated Cyclone Energy in the Atlantic this season. Here's the chart from the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts ECMWF:

The red line shows observed (actual) weather, and the blue line shows predictions. This year's prediction is higher than any other year. This isn't a perfect forecast, because no model is perfect, but it's helpful. It's predicting more, stronger, longer-lasting storms this summer, based on all the physical evidence we have. If that Accumulated Cyclone Energy—twice as much predicted for this year as the average over the last thirty years—is released over coastal US cities, it will come in the form of torrential, nonstop rain, terrifying winds, and destructive storm surge.

Perhaps it's possible to forget or dismiss the drumbeat of news about flooding, sea-level rise, and insurance troubles. Storms just might be more memorable at this point. As coastal real estate becomes a truly liquid asset, a wave of re-pricing is likely.

*This is apparently because of the combination of a warm Atlantic and a La Niña in the Pacific. Dr. Levi Cowan of tropicaltidbits.com tells us that the La Niña in the Pacific makes trade winds (blowing near the equator from east to west) stronger there. At the same time, trade winds in the Atlantic become weaker. In fact, westerly winds will prevail a mile above the surface. The orange in the chart below shows more westerly flow than average in the Atlantic (winds coming from the west) predicted a mile above the ocean for the months of August through October.

At the same time, about 7.5 miles above the surface of the earth, the pattern is reversed: usually, we have strong westerly flow aloft. But these purples show that the westerly wind 7.5 miles up will be weaker than usual. It's been replaced by winds blowing from east to west.

The sharp conflict that usually exists (strong easterlies below v. strong westerlies above) and creates wind shear won't be there, so shear will be lower than average. Imagine a giant pair of shears cutting through a juvenile hurricane and keeping it from growing up. Not happening this summer.

**Watch Dr. Cowan explain these correlations in greater detail here.

—