Why Naples FL Could Lead the Way on Climate Adaptation

With its Boomer population, concentrated wealth, and vulnerability to climate change, the perfect storm is brewing

The Boomers are finally passing from the scene, with the youngest (born in 1964) now either retired or longing to stop working. But there's some conflicting news for younger Boomers this week: US News recommends Naples, FL ("This small town boasts a high quality of life, great weather, and low taxes for retirees"), but Redfin warns that if they buy a condo there they may never be able to sell it again. Condos in the area are sitting on the market an average of 148 days, 83 more days more than last year, and median prices are in decline.

Here's why this cognitive conflict may be highly politically salient. For a host of demographic and climate-related reasons, we should think of Naples as an elderly poster child for changed thinking about climate adaptation. The ferocious effects of climate change will cause entire communities to lose value—which is what is happening in Naples—and as a country we need to be planning now for different, safer places for future retirees to live.

Addressing this now will cost much less than doing it later, which should be an attractive proposition for the solidly-Republican voters of Collier County. The people who carry this message and push for this change should be a nonpartisan bunch. I'm nominating Naples as a hometown for adaptation policy.

Because Naples, known for pickleball and golf and now No. 1 on US News's list of "best places to retire,” is a place where the bill for extreme weather is visibly coming due. Extraordinary development, deferred maintenance, exiting insurers, and accelerating climate threats are having a major effect on the costs of condo living and thus the value of units. Naples is a city where the opportunities created by adaptation will be obvious. In this retiree paradise, there are very strong signals that we need to change how and where we live, and shape laws and incentives that drive those changes.*

Downtown Naples, 1928, from Naples History in Photos.

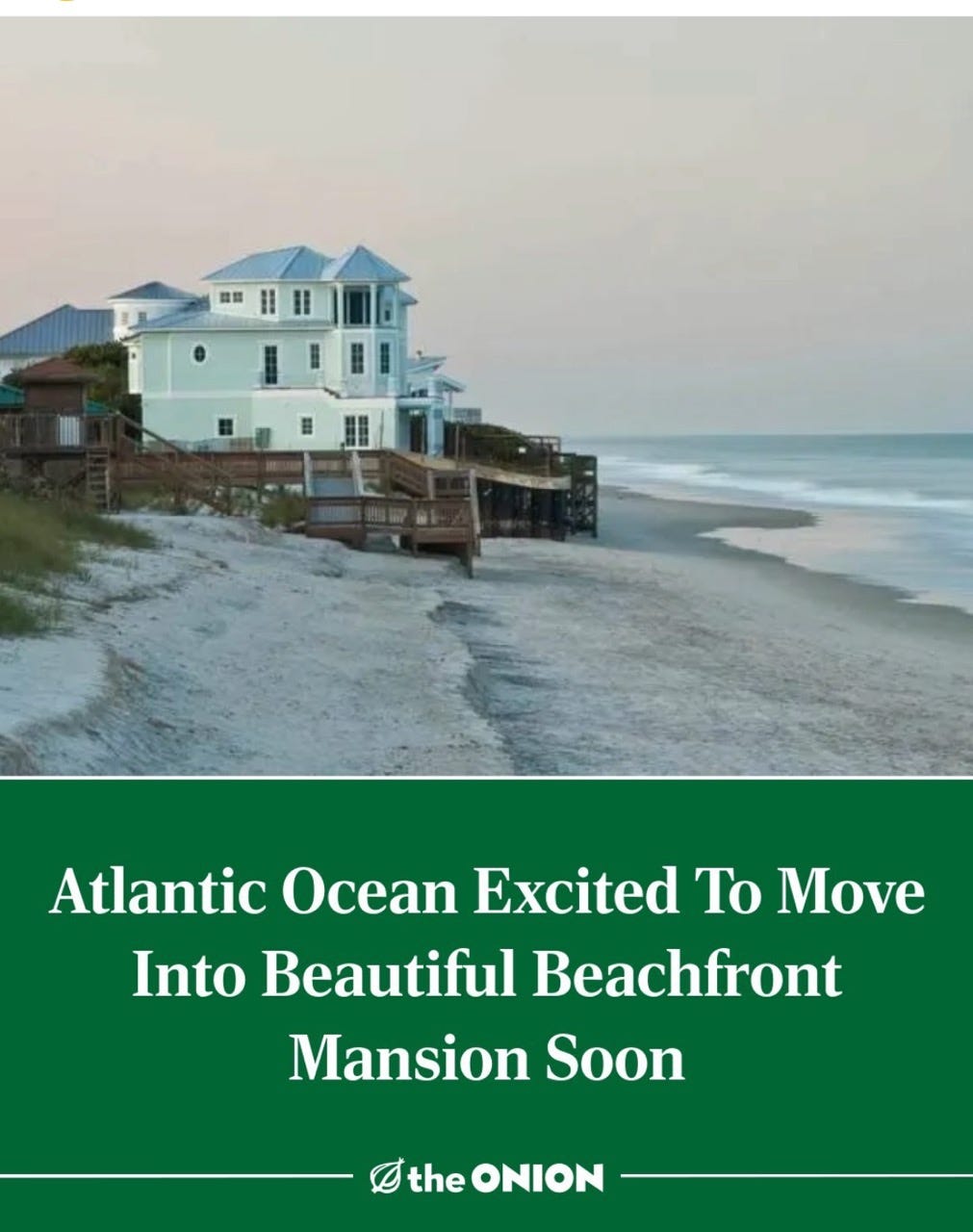

Current VRBO listing in Naples

I'm focusing on the condo market because Boomers love one-floor living. (Never having to climb stairs! The absence of a yard to take care of!) More than half of Naples's residents are over 65. If they live in condos—and many undoubtedly do—they're in a moribund market. I'm thinking they'll care a lot about this.

Condo repair and insurance costs are skyrocketing while listings are flooding in. Some of the condo buildings in Naples have been around for a while. Hurricanes Irma (2017) and Ian (2022) hit Naples hard. Many condo associations haven't been keeping up with maintenance. No one was requiring regular inspections, and condo boards had dominion over what repairs they made and how much they put aside.

Now that's changed: After the collapse of Surfside's Champlain Towers in June 2021, when nearly 100 people were killed, a state law went into effect requiring that all older three-story (and higher) condo buildings be inspected by the end of this year and reserves be put aside for needed repairs. There are large assessments ahead, piled on top of owners' ongoing monthly fees.

At the same time, buildings (and individual owners) are having enormous trouble finding insurance at any price. Insurance rates for condo associations across the state have gone up more than 70 percent on average since 2022, and the climb is likely steeper in Naples. If they can't buy private insurance, they're having to go to the state insurer of last resort, Citizens—which is routinely denying more than half the claims it gets, protected by state law from both (a) liability for behaving badly and (b) lawsuits conducted in courthouses, while also exacting very high premiums.

Some of these owners undoubtedly bought condos in Naples assuming low existing maintenance fees and insurance rates would stay the same forever. Hurricanes Helene and Milton just roared through, and although Naples was spared the worst of the harm, it's been enough—in combination with those other climbing costs—to prompt a lot of people to try to sell. Right now. All at once.

Condos are not selling in Naples. With these looming assessment fees, high and uncertain insurance premia, and floods of listings, all against a background of increasing climate risk, condos are not moving in Naples. The Naples Area Board of Realtors says sales went down 21 percent in September, and the supply of listings is up 54 percent over last year. Many, perhaps most, of those listings are for exactly those older buildings that are subject to the new inspection/repair/reserves law.

Listings are sitting for more than 100 days on average and then selling (if they sell) for significantly below asking price. Luxury properties are particularly afflicted. Foreign investors probably aren't as interested as they used to be. Gov. DeSantis is saying something will be done to help condo owners in trouble, but so far it's not clear what his plan is.

You can hear the rising panic. Listen to this Naples real estate agent, in a video from September 2024 ("The truth about the storms in Naples, Florida”):

"One of the things I really like about the Naples area is it's somewhat insulated [from storms]. You've got Cuba, you've got The Bahamas, depending on which direction it's [the storm] coming, you've got Marco Island, sorry, Marco Island, all of those kind of jut out a little further [into the Gulf]. And even Fort Myers, if you look at a map, it comes out further into the Gulf. Naples is nestled back."

It's quite a performance. Cuba may protect you, we get plenty of warning before the storm hits, evacuation can lead to pleasant stays with relatives ("When we evacuated for Irma, we went to see my brother in Mississippi. It was nice"), you can get tax savings for paying for hurricane protection, and, basically, you're going to love it in Naples. "You can minimize the impact and enjoy your time in this beautiful coastal paradise," she says. "Don't let 'em [storms] scare you off." She's selling into a tough market that has recently gotten tougher.

Although Naples's levels of outright senior poverty are low, many residents living on fixed incomes would probably like to cut their losses and leave. They won't be able to sell easily, or perhaps at all. They may get mad when they suddenly see that a chunk of the wealth they were counting on has eroded, and they will have the wherewithal, the time, and the energy (all that exercise) to make noise about it.

This could be adaptation's moment. This is the theory of change for climate adaptation: when the effects of the changing climate visibly hit investors' pocketbooks in a concentrated way, political systems will pay attention and shift in response. Adaptation is now and should be a nonpartisan issue, particularly in South Florida. Here's a map of where property insurance premiums are climbing the highest (from Mulder and Keys, 2024):

And here's a map of Florida voting results from the election earlier this month:

The blue splotch on the southeast edge of the state is made up of Palm Beach County (to the north) and Broward County (to the south); the red county bordering Broward that is to the west and also bordering the Gulf is Collier County, where Naples sits. Condos in Broward and Palm Beach Counties are also sitting on the market (Broward, Palm Beach County), but the median price for units in Collier County is far higher—$251K in Palm Beach County, $230K in Broward, but $417K for Collier—and so the voices that get raised in Collier may be heard more clearly.

After all, Florida now has the southern White House in Mar-a-Lago. It also has four of the top ten US cities where home prices are going down the most.

Although Hurricane Milton (2024) caused significant damage in Naples and Collier County, it might take one more big storm to push Naples over the edge into adaptation activism. If it takes a crisis to drive policy change—and it seems to—that hurricane is bound to happen sooner rather than later.

Naples: Where a national, nonpartisan climate adaptation push could begin. Naples isn't facing these repricing issues alone. Tampa Bay and Miami, with their many older condo buildings, are also seeing huge upticks in sales inventory. Across the state, according to the Tampa Bay Times, condo listings are up 65% over last year, and median sales prices are dropping. But because Naples has such a concentration of older people, the pain will be felt acutely there. Also, the region around Naples is full of high-income earners—behind only SF, NY, and Austin in the ranking of workers earning at least $500,000 a year.

Here's the idea: Older people vote in huge numbers. They write letters and call their representatives. Wealthy residents cannot stand losing money on their investments. Here's an opportunity to engage right-of-center people on a sensible issue: We cannot protect everyones' property values, but we can learn from the condo market in Naples. These market signals mean that it is getting too risky for new buyers to arrive there. Something has to shift.

We need to incentivize development in relatively safer places so that new buyers have somewhere to go. We need to plan to steadily withdraw public investment from relatively risky places. Most importantly, we need to put the risk on the table and deal with it. As Rep. Garret Graves (R-La.) told the Washington Post way back in 2020, "spending on resilience to prevent costlier climate damage is 'an awesome conservative fiscal argument.'" I'm counting on the residents of Naples to understand this. They surely have the time to reflect and act.

*Not that anyone should stop efforts to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions. This is a both/and story. Whatever we do on emissions, the rapid changes I keep writing about are already here. We're having one of the warmest falls ever. We need to change laws and financial incentives to account for these changes on an ongoing basis.