Alarm bells ringing for Fannie and Freddie

How the property insurance story shows us we're facing a series of 2008s all over again. But this time the underlying housing markets won't bounce back

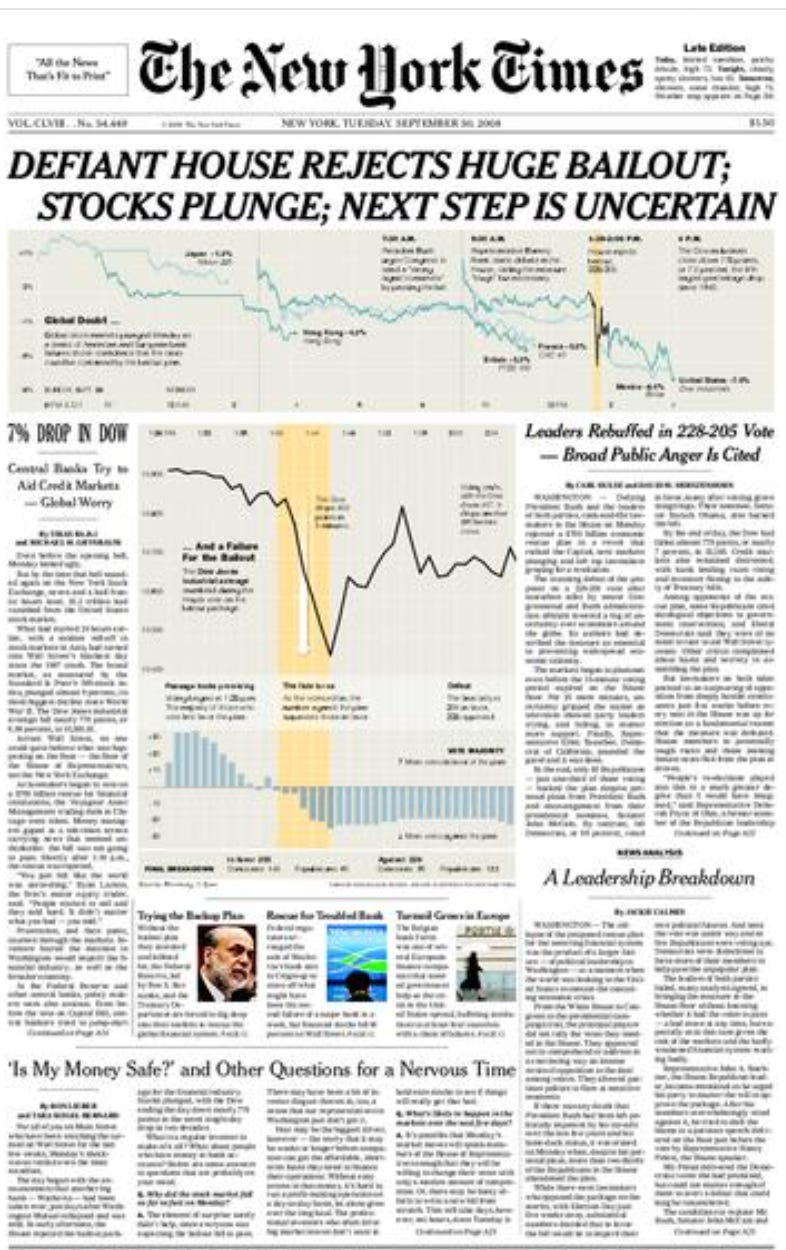

On the next day, a Monday, the stock market crashed. I knew, because I heard it over the radio in a cab, taking the long way from the top of the park. By now, I'd met many people who made their money in the wide field called "finance": bankers, traders, buyers-out, buyers-in, surfers of swelling numbers I couldn't begin to comprehend. Once or twice, Beverly or Ernest had tried to explain to me the particulars of their businesses. My head cottoned up instantly and turned to static. Now, though, I understood well enough that my new acquaintances were in danger..... We usually worked in silence, more or less, except for the murmur of one or two of us on the phone. Now, we had the TV on, scrambling to understand. The biggest crash ever. Each variation of the phrase sounded faker than the last. Perhaps there'd be another Depression. It all had—please forgive me—something to do with housing....

Vinson Cunningham, "Great Expectations," Ch. 13. The speaker is a young man raising money for a political campaign that sounds a lot like Obama 2008.

I'm listening to "Great Expectations" right now. I too remember the morning the market crashed. I remember holding up a copy of the NYT front page in front of my class at UMich the next morning, and the quiet in the classroom at that moment. Like David Hammond, the novel's protagonist, I didn't know what exactly was going on, but I knew it had something to do with housing.

It's now common knowledge that the Great Financial Crisis was triggered by "the corrosion of mortgage-lending standards and the securitization pipeline that transported toxic mortgages from neighborhoods across America to investors around the globe." (Financial Crisis Inquiry Report, Jan. 2011.)

What if we're doing it all over again in pockets of the US, in ways that may eventually infect other areas of the country's financial system? Wouldn't you want regulators to lower this risk?

One key element of the 2008 crisis was the "deeply flawed" model of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, the large, government-backed enterprises (GSEs) that now buy or guarantee most of the mortgages in the US. To be bought or guaranteed by the GSEs, these loans, called "conventional mortgages"—which account for about 72 percent of all home loans—have to meet the GSEs' guidelines. In the run-up to the 2008 crisis, the GSEs, under pressure to both expand homeownership and increase shareholders' returns, relaxed their standards so that they could ingest and securitize riskier loans. These loans eventually became toxic to the global financial system

At the time, the toxicity stemmed from interest-only loans, loans taken out by borrowers with low credit scores, loans with high loan-to-value ratios, loans with high debt-to-income ratios, and loans unaccompanied by paperwork. Today, the problem is different: it's loans that borrowers won't be able, ultimately, to afford because of steeply climbing premiums for property insurance due to climate change.

Increasingly pricy homeowners insurance, with its annual contracts, can make a 30-year-fixed mortgage feel to the homeowner more like an unconstrained, ballooning adjustable loan. In effect, the repricing of risk that climate change should logically cause is already happening in insurance markets—because they're more liquid, less supervised, than other parts of the financial system. This regular, sharp repricing of risk makes it more likely that people in risky pockets of the country will walk away from loan obligations connected to homes that are simultaneously swiftly losing value. Even if owners are able to sell those homes, any new buyers will also have trouble with rapid insurance increases.*

All of this might make you look around for a regulatory cordon that can contain or lower the risk of this repricing. Maybe people really shouldn't be getting mortgages they won't be able to afford.

One clear break point resides in the standards or guidelines adopted by GSEs. The last time around, lower GSE standards arguably encouraged banks to write risky loans—because the federal government was willing to guarantee or buy up those mortgages. As the final report on the 2008 crisis said, "Lax mortgage regulation and collapsing mortgage-lending standards and practices created conditions that were ripe for mortgage fraud."

So this time we should look for tighter guidelines that send the signal to stop handing out potentially toxic loans whose unsustainability is driven by rapid climate change being (appropriately) priced into insurance premiums. That toxicity won't be obvious to borrowers—they don't have access to the models the insurance companies use. Nor should it be individual consumers' burden to guess about climate risk.

In February of this year, regulators took a step toward tightening GSE guidelines to reflect risk. Fannie Mae announced that it was "clarifying" its property insurance requirements for conventional mortgages as of June 1, 2024 by requiring that policies pay losses on a "replacement cost basis," instead of any other measure (like, say, the depreciated cost that someone might be willing to pay for the damaged or destroyed property).**

In other words, in order for a mortgage to be acceptable to Fannie Mae, property insurance associated with the loan (and property insurance always has to be part of the package) had to cover the estimated costs to rebuild the property back to its current state in case of a disaster. Fannie Mae said it was doing this "at the direction of" its regulator, the Federal Housing Finance Authority (FHFA). It also said there would have to be an annual verification of this full replacement-value coverage.

From the lay perspective, this seems like a good idea. For the insurance signal to do its job in constraining both lenders and borrowers, it should reflect the reality of climate change. If insurance payouts are limited to the damage-depreciated value of a house, that means two things: First, the market signal ("insurance for this house is really prohibitively expensive!") is muted. Second, if there is an extreme weather event borrowers will be inadequately protected. They'll be on their own.

You'd think lenders would want this protection, right? It will be frustrating for people in risky places to feel that insurance is too expensive, but wouldn't it be better to have that pain be felt before someone signs up for a mortgage that locks them into an unsustainable future?

The insurance industry did not agree, and last month sent a bristling nine-page letter to the FHFA director, Sandra Thompson. It looks as if a number of Florida insurance carriers have been offering depreciated payouts for roofs, in particular, "as a way to reduce losses and give homeowners and option to mitigate premium increases." More broadly, the industry really doesn't want aggressive enforcement or mandates, including frequent lender requests for updated valuations, right now.

But, for me, the big takeaway from the industry's complaints was this (paraphrasing): "If you do this, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, you'll be effectively undermining the state-run insurance oversight we have!" The language of this letter sounds like a threat to sue, to my ears: "In fact, these GSE changes appear to impair, conflict with, or supersede state insurance laws and regulations; they potentially create conflict under the McCarran-Ferguson Act’s delegation of insurance regulation to the states."

You don't need to know a thing about the McCarran-Ferguson Act to grasp what's going on here: The federal GSEs don't regulate insurance companies. They set standards for the loans they'll accept onto the public's books. Nonetheless, the insurance companies are complaining that having to meet existing FHFA standards that are aimed at protecting lenders and borrowers from toxic loans is somehow unfair.

Why? Because all their oversight comes from state insurance commissioners. And having a fractured, no-best-practices, make-friends-with-your-state-regulator system has been great for the very lucrative homeowners insurance industry (and great for Berkshire Hathaway, and great for private equity). They don't want the secondary mortgage market that drives lending in the first place to mess up their business.

At the end of April, an industry trade group lobbyist told members they were "putting congressional pressure" on the FHFA to delay the June 1 effective date. Apparently the effort worked: earlier this month, FHFA backed off, saying it was pausing enforcement of the requirement that lenders figure out whether insurers pay losses based on the replacement cost of a given property, but not the requirement itself (which it said had been in place for a while).

Look, this is just part of a much larger story. This isn't the end of the drama surrounding the GSE guidelines. And, more broadly, if we're going to have sensible federal policy that sets tough priorities for adaptation, we'll need federal agencies to be able to limit the risks faced by the entire country.

There should be alarm bells going off about these potentially toxic mortgages. The repricing of risk that we're seeing first in insurance markets will eventually be reflected in property values themselves. Unlike the last time around, those property values won't be rebounding. Climate change is here to stay.

Kudos to the FHFA for trying.

* Listen to Dave Burt, who foresaw the collapse of the subprime mortgage market the last time around. He was interviewed by Amy Scott on Marketplace earlier this week:

Amy Scott: Now, nearly 20 years later, Burt thinks the market is due for another correction, as homeowners in places with growing risk of flooding and wildfire have to pay more for insurance.

Dave Burt: This is actually happening right now, and is probably going to happen over the next three to five years, like a full reckoning of these new costs for 15 or 20 percent of the homes in the US....If all their equity is already gone [because of lowered property values]. Their costs are going up a ton. They can barely afford it. That's when people walk away.

**The Selling Guide published by Fannie Mae is here. To find the part about property insurance, go to Chapter B7-3. Another aside: You'll see Demotech's ratings have to be A or higher for a mortgage to be acceptable, while lower grades from the other rating agencies are acceptable—which connects to the credit-rating worry I wrote about a while ago.